The Book is Dead. Long Live the Book.

A current exhibit at Princeton University takes us into the work and ideas of a revolutionary literary mind.

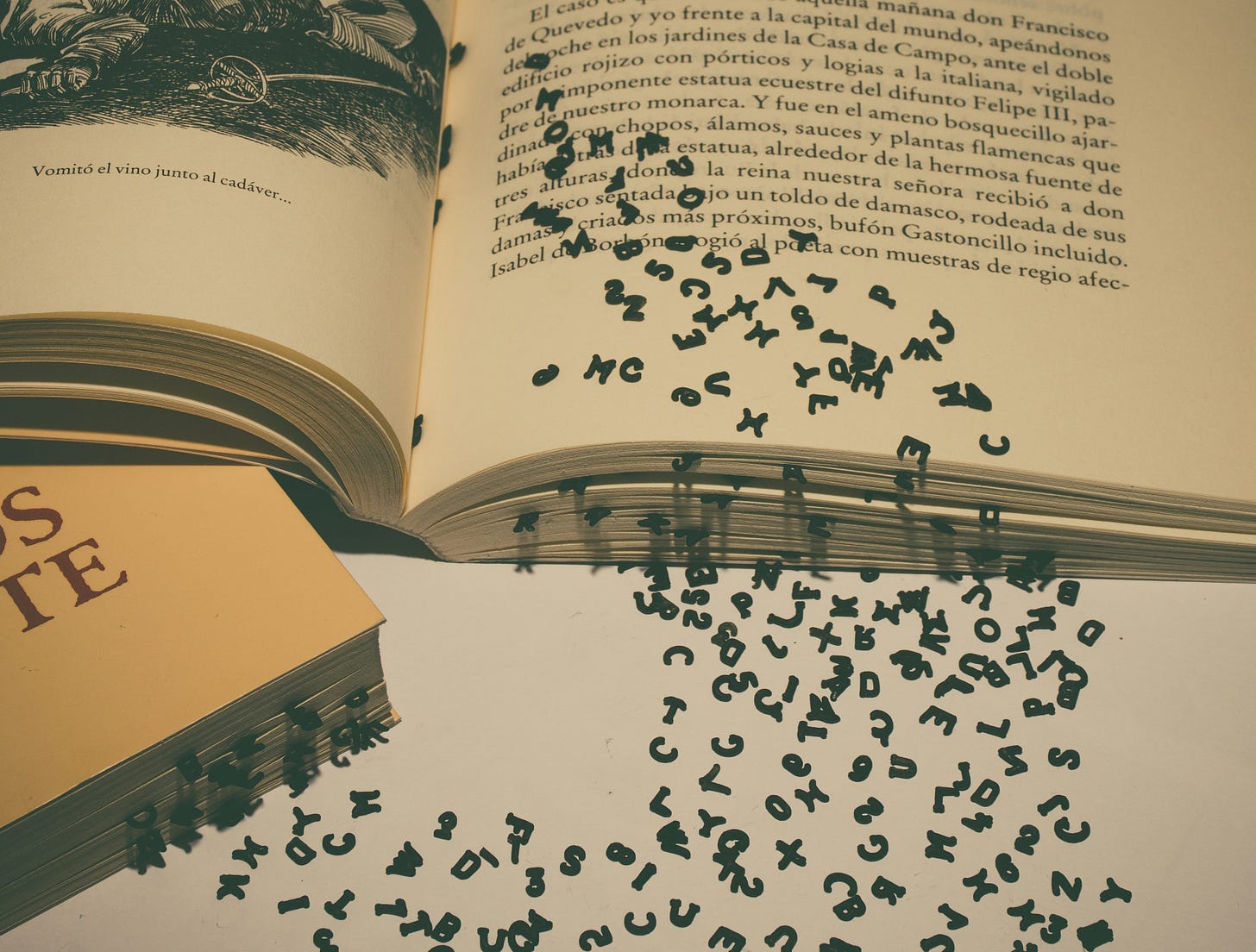

Books were a dirty job, one of the black arts, along with witchcraft and printing.

―Sara Gran, The Book of the Most Precious Substance

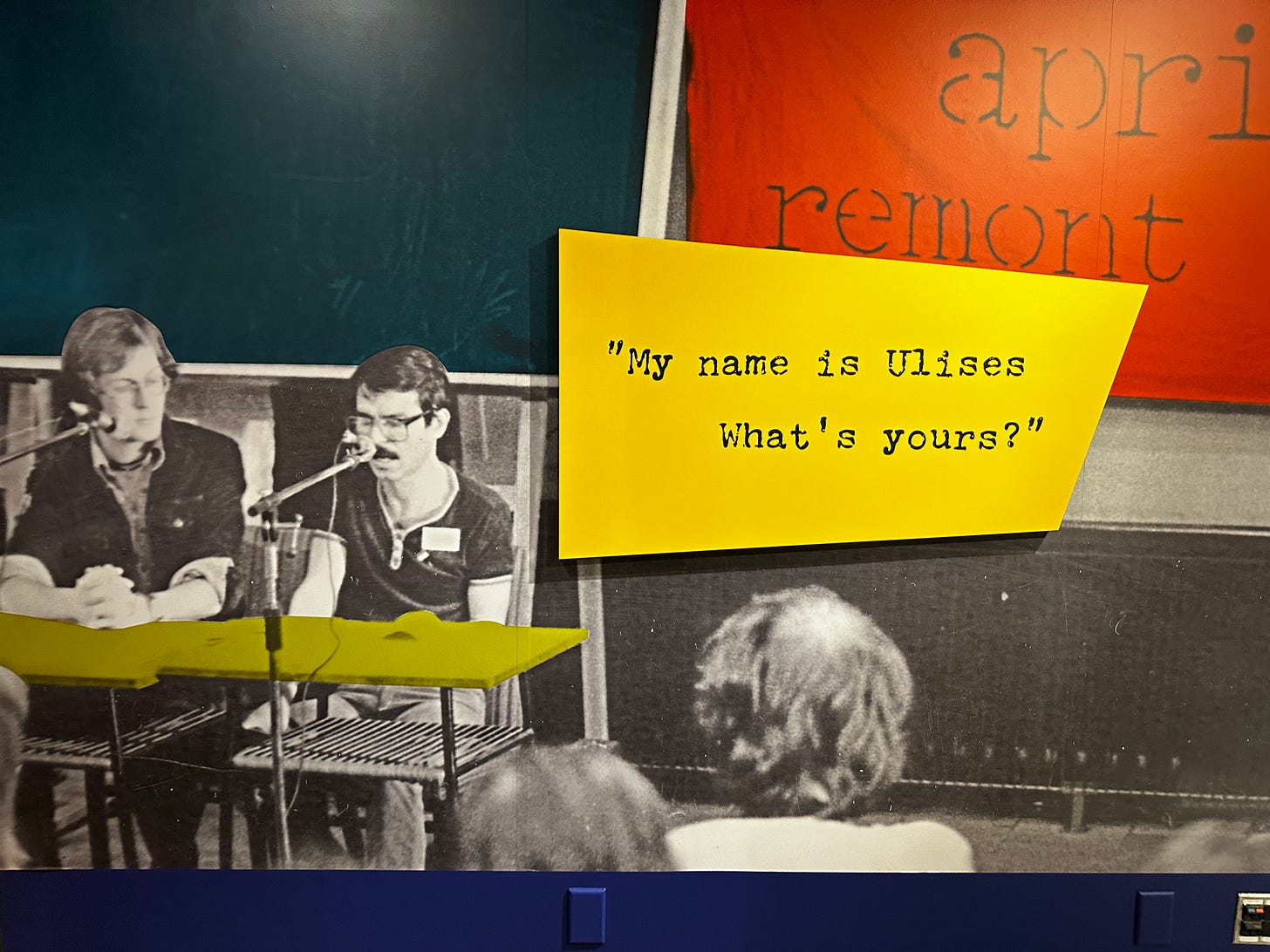

In a recent post, I mentioned the work and ideas of the Mexican conceptual artist Ulises Carrión. On Wednesday, I drove up to the Firestone Library at Princeton University to see a new exhibition of Carrión’s work. Entitled “Bookworks and Beyond,” the exhibit presents many of his pieces and surveys some of the most essential concepts that animated his work. On the day I was there, I was fortunate to attend a “scholarly discussion” on Carrión’s legacy and influence, which shed further light on his creations and personal life.

Born in 1941, Carrión started his literary career in traditional form, publishing stories in some of Mexico’s most respected journals and outlets while still in his twenties. At the start of the 1960s, he corresponded with leading Mexican writers and seemed poised for a notable literary career. However, that path had changed dramatically by the end of the decade. Carrión abandoned both Mexico and writing traditional literature. He gave away all his books to friends, left his native land for Europe, and vowed to “wage war on literature” elsewhere.

That he left Mexico probably came as no surprise to those who knew him well, given an episode from his childhood that Carrión recounted:

As a four- or five-year old child, I often asked my parents if they would like to give me away to another family, to the neighbors, or to some relatives. Not that I disliked my own family, far from it. But I found the idea vulgar, intolerable, that one could not choose one’s own family. It was much later that I came to realize that I was not opposed to the family, as such; rather, I simply couldn’t stand not being able to determine one’s own destiny. I loathed having boundaries placed on one’s personal freedom. Even at an ealy age I knew I would go away. In the beginning, this usually meant “away from this city”—from my birthplace. Later, when I had learned the concept of nationality, it meant “away from this country.” I had the deep conviction that wether you were born here or there was a matter of pure conincidence. My brothers and sisters didn’t like my ideas at all, and so as a joke they would give me as a present to the neighbors. After a couple of hours I would return home on my own. Now I know that the reason I didn’t stay long at the neigbors was that they weren’t different enough either.”1

After spending time in various European cities, Carrión settled in Amsterdam, where he founded “Other Books and So,” the first bookstore dedicated to artists’ books. The word “Other” in the store’s name is essential, for it encompassed, Carrión explained, “non-books, anti-books, pseudo-books, quasi-books, concrete books, visual books, conceptual books, structural books, project books, statement books, [and] instruction books.”2 The “and So” in the title referred to other things he presented: recordings, postcards, graphic works, and objects that fit no known category.

Other Books and So was to be the nexus of a career in which Carrión would challenge himself and his audiences to disconnect themselves from the traditional idea of a book as solely the words of an author and to see a text as one of many elements that (can) make up a book. As Carrión put it: “A writer, contrary to the popular opinion, does not write books. A writer writes texts.”3

To make a book is to actualize its ideal space-time sequence by means of the creation of a parallel sequence of signs, be it linguistic or other.

―Ulises Carrión, “The New Art of Making Books”

Carrión called many of his creations bookworks, and they demonstrate so much imagination and provocation that it is hard to know where to start. Consider, for example, “Tell me what sort of wallpaper your room has and I will tell you who you are.” Each page of the volume presents a piece of wallpaper that is supposed to have come from the bedroom of the person named on the page.

The work is a series of spaces in which we confront both text and image. It is a public work, yet it is also a glimpse into someone’s private world. Like the Edward Hopper paintings focused on windows, we stand outside looking in, our minds building a story around each page. Through this creative act, we become authors of our version of the stories; we supply, in other words, the text to complete Carrión’s book.

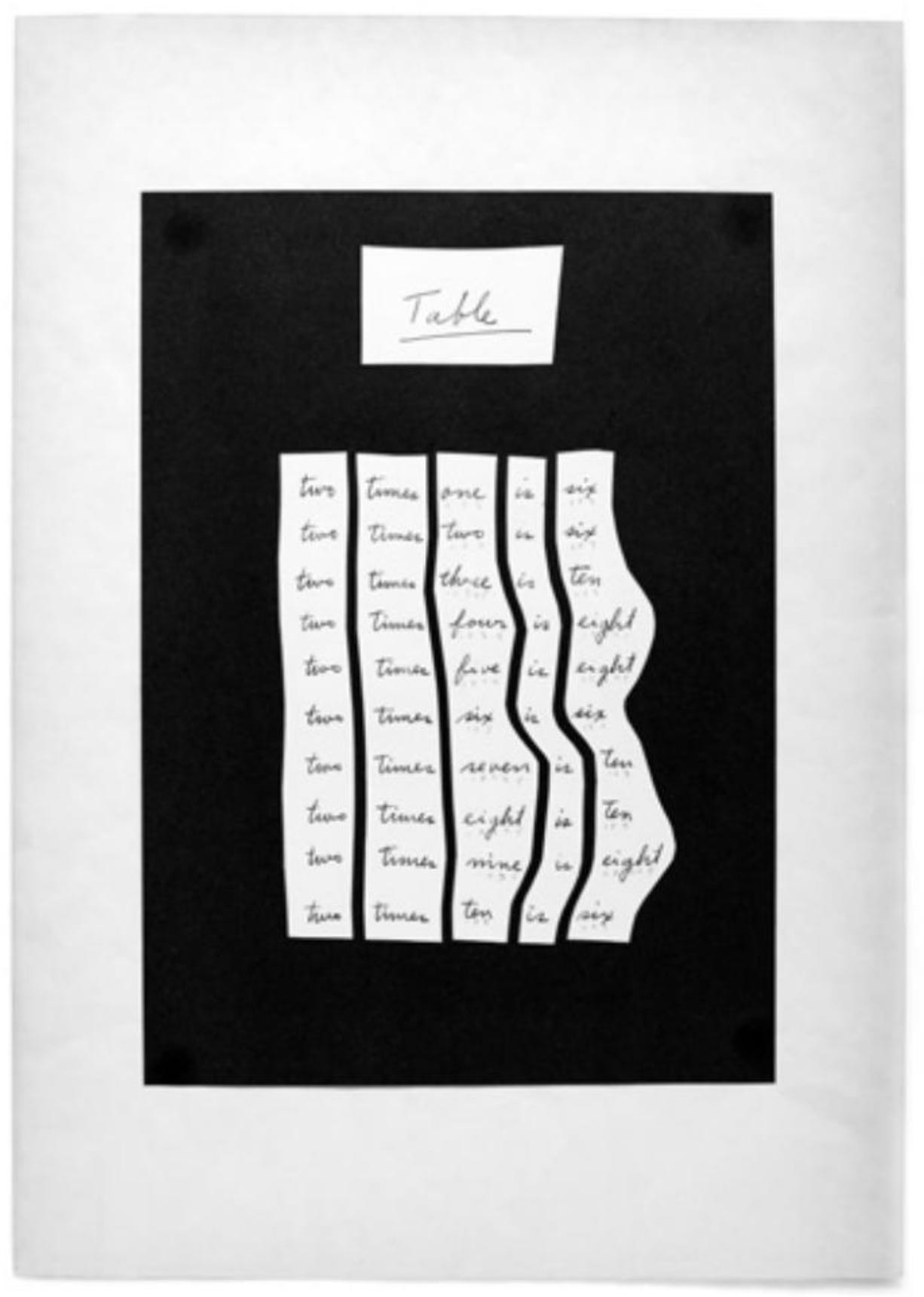

Consider, as well, a page called “Table,” from another bookwork. It presents the “2 x 1-10” table we learn as children, but only the “two” and “times” columns are visually stable. The other columns bend outward and inward as the table progresses vertically, with the “answer” column experiencing the most substantial deformations.

What is “Table” saying or asking? Is it a statement about the illusion of mathematical certainty? Is it a commentary on our capacity to hold information? Is the title itself a sly joke, with the word “Table” sitting on a line that could be a tabletop? Is the black field also a tabletop on which the columns have been spread out and on which they have started to change shape? It is only one page from one bookwork, but we could discuss it for hours and reach no conclusions. The critical part, I think, is that the page’s printed form alters (one could say “rewrites”) the meaning of the text, which is, again, but one element of what makes up the book’s identity. The text does not reign—it is, at best, primer inter pares.

Old art’s authors have the gift for language, the talent for language, the ease for language. For new art’s authors language is an enigma, a problem; the book hints at ways to solve it.

―Ulises Carrión, “The New Art of Making Books”

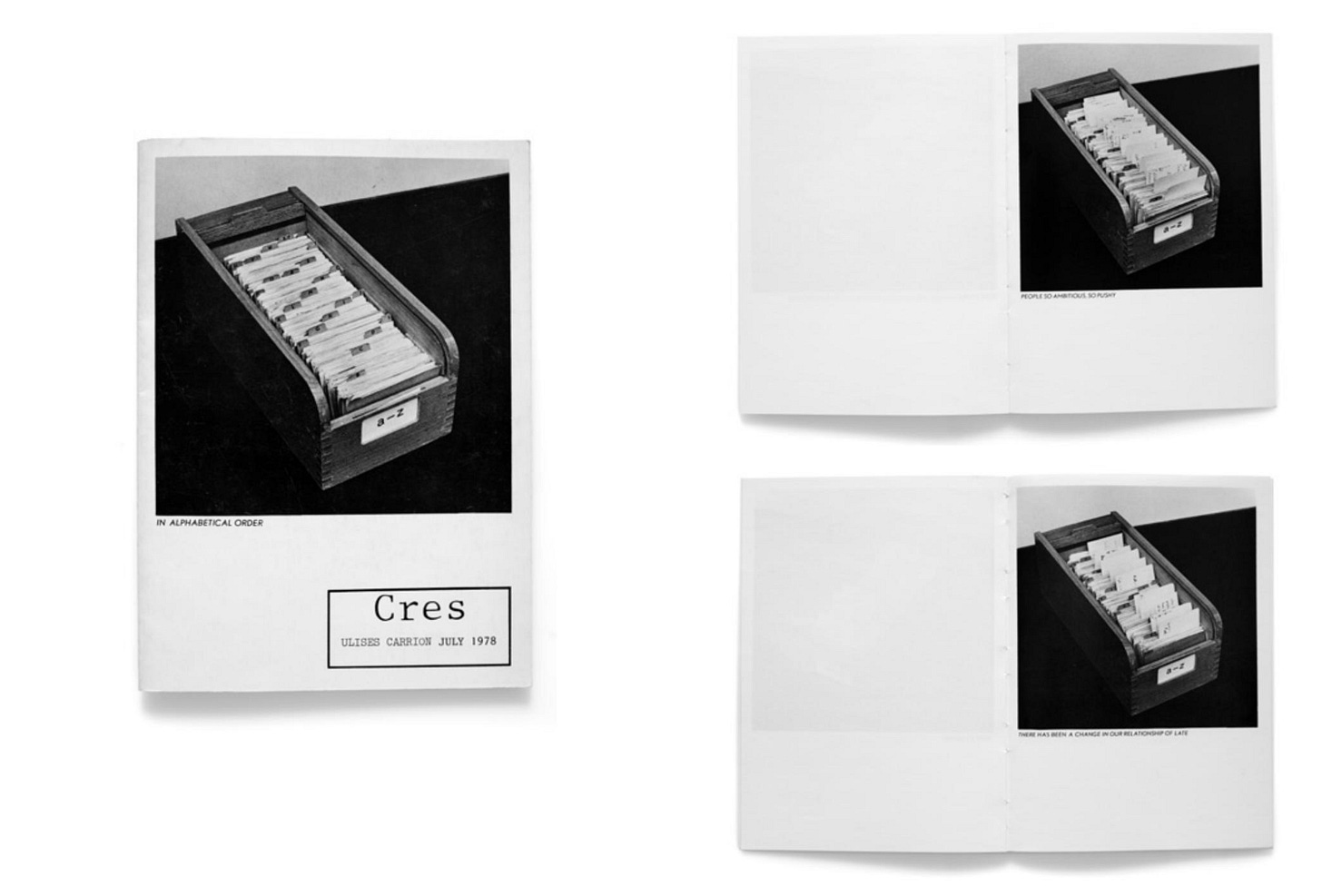

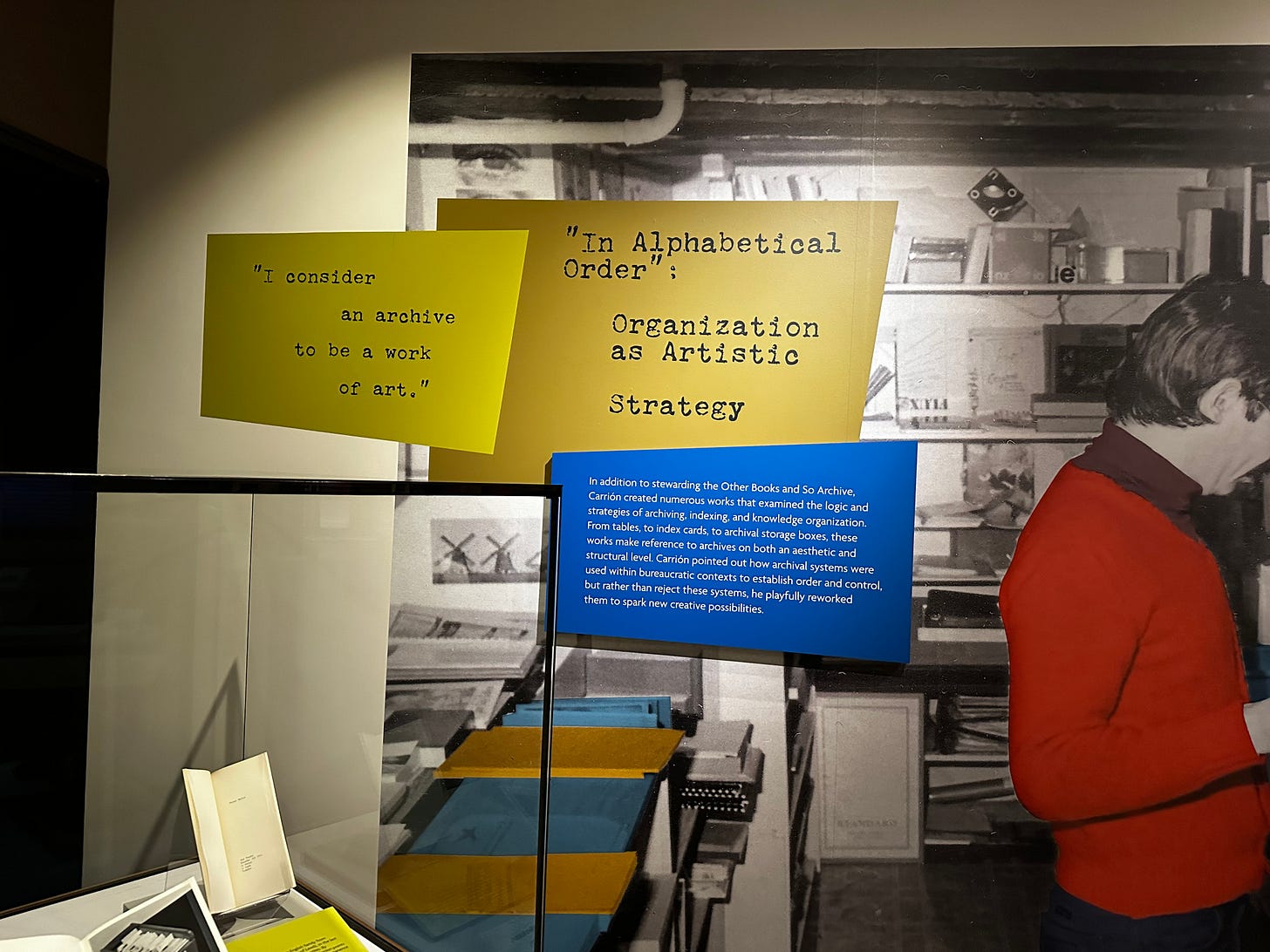

Of all the Carrión works I have seen, my favorite is “In Alphabetical Order,” which he created with Cres Publishers in 1978. It contains photos of Carrión’s personal rolodex, containing over a thousand index cards, on each of which is written the name of someone in his world (some with codes signifying professional role and the medium in which the person worked, traded, sold, collected, critiqued, etc.). Carrión shows us alternate versions of his archive of human connections. In the first version, all the cards are placed horizontally in simple alphabetical order. In other versions, selected cards are placed vertically and then identified with text: “People I’ve Met; Artists; Non-Artists; My Best Friends-People I Love; People I Admire; There Has Been A Change In Our Relationship Of Late,” etc.

Looking at “In Alphabetical Order” at the Princeton exhibit, it suddenly became clear to me how this creation is also a “book”—indeed, an amazing one. Through the simple act of categorization, Carrión brings a narrative to life in which his world is segmented into artists (and thus like him?), non-artists (and thus not like him?), the loved (are the rest not loved?), and, mysteriously, those whose relationship with him is not what it once was (for the better or worse?). Looking at the work, I imagined being able to divide the contacts in my phone in such a way and wondered what my categories would be: “People I love; People Who Sold Me Something; Writers; Non-Writers; Scholars; Business People; People I Don’t Remember; People I Can’t Forget.” Each segmentation creates a new set of characters and, thus, a new narrative of my life—each a unique combination of reality, memory, and imagination. As Carrión notes about his collection: “This book of mine is partly real facts and partly fantasy.”

One feature of the Princeton exhibit is that it also presents examples of Carrión’s work in what is known as “mail art,” which is just what it sounds like: an artist uses the postal system to create something, often involving the mail art’s recipients.

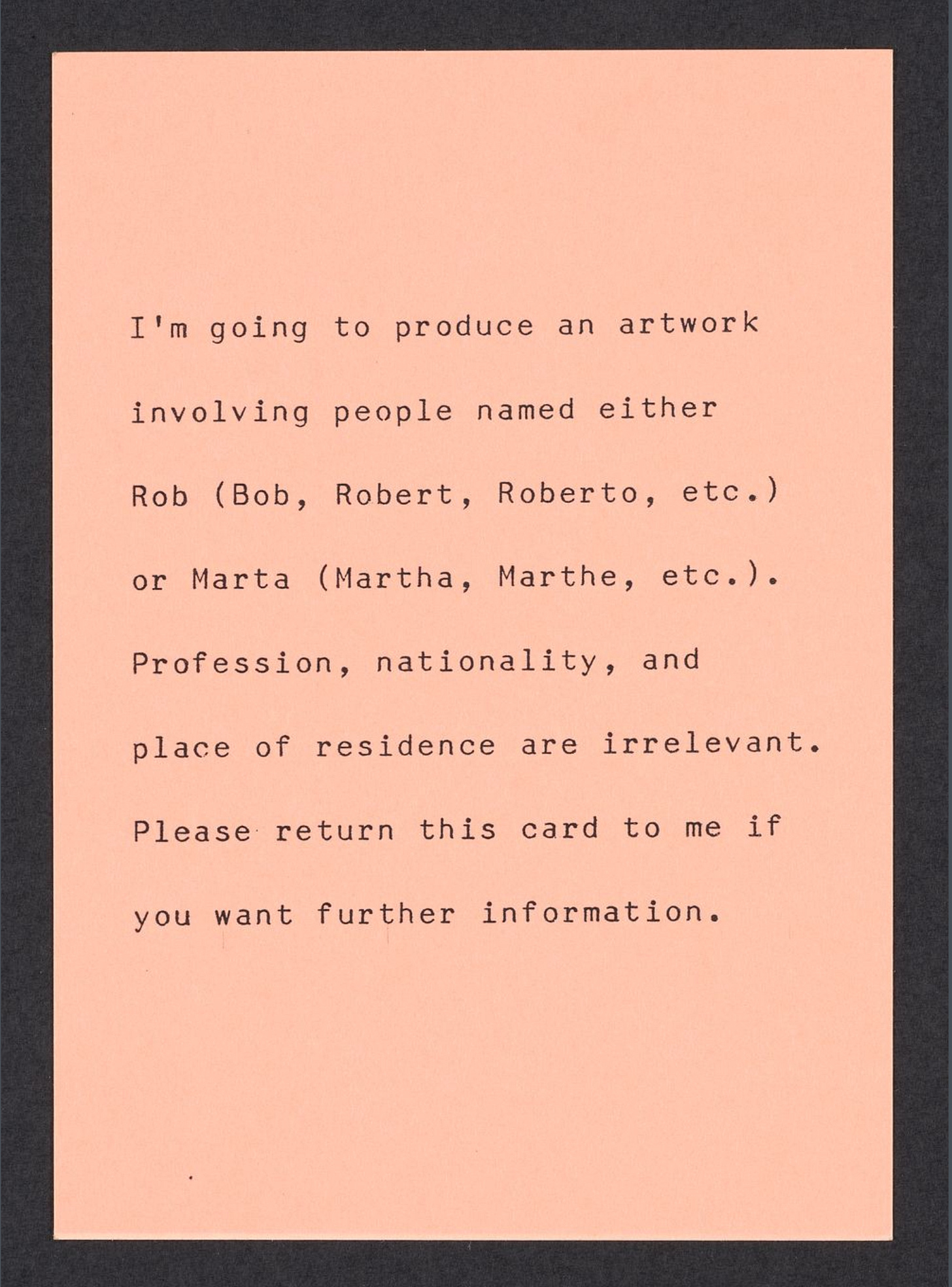

Carrión created several mail artworks, some of which can be seen in the digital version of the Princeton exhibit. His creations range from serious pieces to tongue-in-cheek projects. In 1983, he sent out his last mail art project, which had only one rule, as you can see below:

The recipients were randomly selected, and Carrión sent dozens of these postcards to various “Robs” and “Martas.”

Why seek help from random people? Here, in part, is Carrión’s answer:

Why is the artist asking for answers from other individuals instead of giving himself multiple answers? He has indeed renounced the possibility of a unique answer. The necessity of giving multiple answers is then revealed, concretised by the plurality of sources. From this point of view, a Mail-Art project is never closed. Every human being, even those who will never hear the question, can provide an infinite number of possible answers. And here intervenes perhaps the most crucial element in a Mail-Art project - showing the answers to an audience. The artist should convince the audience that they are looking at him, that every piece in the show, that all these apparently unconnected pieces coming from various sources and with various purposes, are a true reflection of himself.4

Such projects represented models of what Carrión called “cultural strategies,” a term he used to signify how art helps us shape and give meaning to the world.5 A cultural strategy was a way to answer a question such as, “Where does the border lie between an artist’s work and the actual organization and distribution of the work?”6

In order to be able to read the new art, and to understand it, you don’t need to spend five years in a Faculty of English.

―Ulises Carrión, “The New Art of Making Books”

Reflecting on “Rob and Marta,” I find it intriguing that most replies that came back to Carrión were from people with other names who ignored his straightforward request. For some reason, these people felt the need to be a “Rob” or “Marta” in the context of Carrión’s project. Was this phenomenon a counter-narrative subversion of his art? Was it a joke placed on top of what they saw as his joke? I don’t know the answer to these questions, but “Rob and Marta” reminds me that an artist may possess intention, but the audience confers purpose.

During the Q&A after the discussion, an audience member asked Professor Mónica de la Torre why Carrión is suddenly so popular after decades of obscurity. She replied that after he died of AIDS in 1989, his work did not receive wide scholarly attention. In 2016, the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid presented an exposition of his life and work, bringing many previously unknown works (and information on his life) to light. Since then, she added with a smile as she (and one of the other panelists) held up a tote bag with an unsigned Carrión quote printed on it, a kind of “secret cult” has formed around him and his work. Someone else then asked if she could explain the attraction, to which she replied that it is because Carrión seems to speak to each person who discovers him in a way not shared with anyone else. Perhaps because he asked questions as much as he gave answers, she added, and often invited the audience to be part of his creative process, we can interact with his work uniquely and personally. Professor de la Torre is correct. Walking through the Princeton exhibit was like conversing with Carrión, and I could imagine him watching me as I studied each exhibit.

“Dear Reader. Don’t Read.” is Carrión’s most famous quote, and I understand it now. To readers, he urged: don’t read a text and ignore the book; don’t revere the writer and ignore the printer; don’t consume others’ stories (not even his), when you can create your own with something as simple as a postcard; and remember that a book is not a text. A book is what Carrión called a “space-time sequence” that we fill through intellectual and physical labor.7 The book’s magic lies in how these spaces, once bound in form and spirit, take our stories—in words and pictures, answers and questions, realities and dreams—and bring them to life.

ULISES CARRIÓN BOGARD

1941: Born in San Adres Tuxtla, Veracruz, Mexio

1960: Settles in Mexico City; studies philosophy and literature at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (UNAM)

1963-64: Grant for studies at the Centro Mexicano de Escritores, Mexico City

1964-66: Grants for language and literature studies at the Sorbonne in Paris and the Goethe Institute in Achenmühle, Germany

1971-72: Grants for language and literature studies at the University of Leeds (postgraduate diploma)

1972: Permanently settles in Amsterdam, where he co-founds the In-Out Center (1972-74)

1975: Founds the bookshop-gallery Other Books and So (1975-79), later Other Books and So Archive (1979-89), in Amsterdam

1983: Co-founds Vereniging van Videokunstenaars, later Time Based Arts (1983-93), in Amsterdam

1984: Receives Dutch citizenship

1989: Dies in Amsterdam

This story appears in Guy Schraenen’s essay, “A Story to Remember,” for the Reina Sofia exhibition’s excellent companion book available here.

Advertisement for “Other Books and So,” 1975. An interesting example of “and So” is Carrión’s “Hamlet for Two Voices” (1977) in which two performers read aloud the names of the characters in Shakespeare’s play as they appear in the text:

Schraenen, “A Story to Remember.”

From Carrión’s introduction to the Postage Stamps and Cancellation Stamps Exhibition.

For a detailed discussion of Carrión’s concept of cultural strategy, see “Beyond Bookworks: Ulises Carrión’s Cultural Strategies” by Sarah E. Hamerman (Master’s Thesis, School of Liberal Arts and Sciences Pratt Institute, 2017).

Ulises Carrión, Second Thoughts (Amsterdam: VOID Distributors, 1980), p. 51.

Ulises Carrión, “The New Art of Making Books” (Kontexts no. 6-7, 1975), p.1.