On the Secrets of (and in) Books

A seminar on the "history and futures of the book" suggests just how special books are and can be.

Everything in the world exists in order to end up as a book.

―Stéphane Mallarmé, “The Book, Spiritual Instrument”

One of the joys of returning to school is the chance to learn from scholars who devote their lives to understanding aspects of our world at a level far beyond what we would normally encounter. In a lifetime spent studying a genre, era, or artist, a scholar can develop a profound understanding of a subject that, when shared, illuminates what is often unseen to the average person. This semester, I am in a seminar on the “history and futures of the book” with Dr. Matthew G. Kirchenbaum, Professor of English and Digital Studies at the University of Maryland and a member of the teaching faculty at the University of Virginia’s Rare Book School. Professor Kirchenbaum has been a Guggenheim and NEH Fellow and is co-founder and co-director of BookLab, a “makerspace, studio, library, and press devoted to what is surely our discipline’s most iconic artifact, the codex book.”

In our readings, I come across aspects of book history, creation, use, or conceptualization that I find fascinating. In this week’s class readings, for example, I learned about collation, which refers to an intricate method of comparing copies of texts, trying to find any moments where the texts differ. For textual scholars, collation helps establish issues such as authenticity and primacy, as well as to establish what is known as the stemma of a manuscript—a sort of family tree—to reconstruct the original text.

For book scholars, collation is used to analyze a book’s physical construction and properties. Sarah Werner of the Folger Shakespeare Library describes the method thus:

For bibliographers and catalogers, a book’s collation is a formulaic description of the physical book, including information about its format, the order of its gatherings (the register), and the number of leaves. It’s useful information in terms of understanding what you’re looking at. Is this copy missing leaves? Is this the state that includes the second variant on the title page? A collation formula can help you know what you’re going to see before you even look at a book.

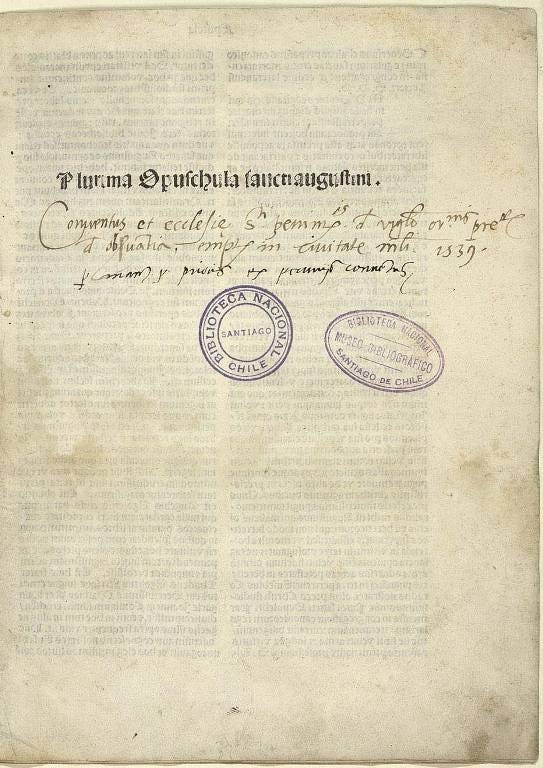

Below is the collational formula for a 1491 edition of Augustine’s Plurima Opuschula Sancti:

4°: []2, a-q8, r4 (n2 unsigned)

Werner explains how to read the formula as follows:

In less oblique language, this describes the book as being in a quarto format (4°), as starting with two blank leaves ([]2) followed by 16 gatherings (because, of course, j was not used) labeled alphabetically a through q with each gathering consisting of 8 leaves (a-q8), followed by a gathering labeled r consisting of 4 leaves (r4), with the additional information that the second leaf in the n gathering does not have a signature mark on it (n2 unsigned).

The formula for this collection of some of Augustine’s “minor works” is pretty simple. Other formulas, notes Werner, are more complex. For example, here is the collation formula for what is known as the First Folio — the first edition of Shakespeare’s works published seven years after his death:

2°: πA⁶(πA1+1, πA5+1.2), A-2B6, 2C2, a-g6, χ2g8, h-v6, x4, “gg3.4″(±”gg3”), ¶-2¶6, 3¶1, 2a-2f6, 2g2, “Gg6“, 2h6, 2k-3b61

I’ve long been fascinated by systems of coding/encoding, so I enjoyed learning about collation. Looking up more information on the process, I discovered that in the medieval Benedictine tradition, a collation was a light meal allowed during times of fasting and that its name was derived from John Cassian's Collationes Patrum in Scetica Eremo Commorantium (“Conferences with the Egyptian hermits”), a book from which the monks gave readings before eating.2

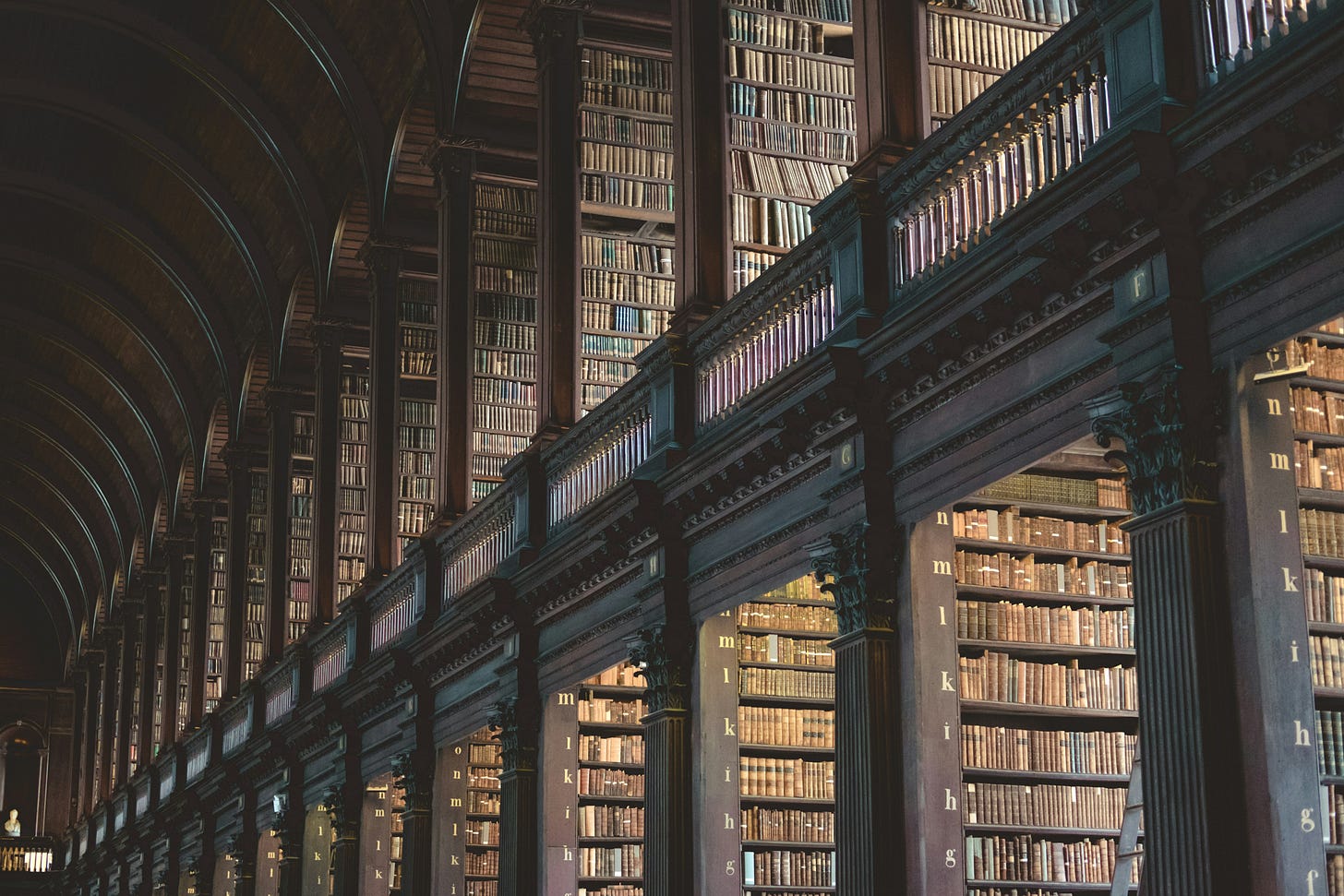

I can’t help but think of our weekly seminar in the BookLab as a kind of collation, in which, to use Werner’s words when discussing the daily 3 pm tea break at the Folger, “we gather to meet new ideas and brainstorm about discoveries in the vaults.” Perhaps owing to its cloistered origins or because those who handle books professionally may come across works that are banned, evil, sacred, rare, etc., it seems that “bookishness,” to use the scholar Jessica Pressman’s term, has an aura of mystery and ritualism that many of its adherents relish. It is a kind of secret society around which a high barrier is placed to keep out those unworthy of participating.

It is easy to imagine that all old bookshops and libraries have a “front/public” room and a “back/secret” room where the really interesting books are housed. Even in our class, I sometimes get the sense that we are peering into secret spaces, learning mystical codes, and thinking about books in ways that are strange, odd, and perhaps even subversive. Indeed, when I describe this class to some of my friends, many just shake their heads and ask something like, “why on earth would you want to study all that?” Listening to their reactions, I can’t help but wonder if bookishness is “elitist,” and, if so, whether in the good or bad sense of that word (I think it has both). Is bookishness dangerous, even? I ask that question as I recall the films—including Roman Polanski’s The Ninth Gate, Jean-Jacques Annaud’s The Name of the Rose, and Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden—in which a character is obsessed with books, and that obsession is the foundation of his/her moral corruption.

For devoted writers and readers, the book holds a special place in their minds and hearts. They hold on to them and feel comforted in the surroundings of a great library. They marvel at lovely editions and hold dear the lessons and stories they contain. As a writer, I thought I understood what books are, yet only three weeks into the term, I am forced to reconsider some of my basic assumptions of what a book is, how it functions, and what it represents. The most provocative reading to date has been a work by the Mexican visual artist Ulises Carrión entitled The New Art of Making Books. In an essay on Carrion, the writer and scholar Amaranth Borsuk describes the genesis of the work:

Demanding that writers take a more active role in the conceptualization of their books, he published “The New Art of Making Books” (1975), a manifesto whose polemical tone served as a provocation that still irks some readers today. Originally written in Spanish and published in Plural, the magazine founded by Octavio Paz, it was aimed at a literary audience Carrión felt needed a jolt. Disavowing the novel as “a book where nothing happens,” and proclaiming “there is not and will not be new literature anymore,” he clearly hoped to ruffle feathers. The novel, of course, is not dead, and it still serves an important expressive purpose, but Carrión’s reenvisioning of the capacities of the book show us much about the ways artists’ books have helped multiply its possibilities by treating the book as an intermedial space.3

Borsuk notes that, like Stéphane Mallarmé before him, “Carrión saw the page’s spatial potential.” His manifesto opens with the following line: “A book is a sequence of spaces,” a definition, adds Borsuk, “so porous as to allow for any number of objects or artifacts we might think of as books: a bound codex, a deck of cards, or a series of rooms.” But she continues, “his definition stretches still further: ‘Each of these spaces is perceived at a different moment—a book is also a sequence of moments.’” Carrión’s expansive and provocative conception of what constitutes a “book” is illustrated well in a video called “bookworks,” the trailer of which is presented below.4

I must confess that I was indeed “irked” and had strong (often negative) reactions to Carrión’s essay. Though I appreciated the larger points he presented about form, text, art, and language, I did not always like how he made them. On first reading, I thought some of his ideas displayed a degree of naïve absolutism that ranged from misinformed to arrogant to confusing. For example, he writes that “just as the ultimate meaning of words is indefinable, so the author's intention is unfathomable.” His claim struck me as a misunderstanding of intention. An author’s intent may be very clear from her very own words. That does not mean that her intent is correctly stated or that it is or is not achieved, but that is far from concluding that the work of all authors — in all places and times — is “unfathomable.” In such a world, writing — including Carrión’s own — would be meaningless. Moreover, claiming that “the most beautiful and perfect book in the world is a book with only blank pages, in the same way that the most complete language is that which lies beyond all that the words of a man can say” seemed a somewhat trite observation. I could easily follow his claim with the statement that the most perfect music is the one with no notes, and the most perfect painting is a blank canvas, etc. Moreover, to say that “everything that exists is a structure” displays a misunderstanding of the physical world. Everything that exists is not a structure, as quantum theory teaches us. We might say that everything that exists does so in a structure, assuming that the universe is itself the ultimate “structure,” but that is a different claim.

At the start of our seminar, I expressed my dislike of Carrión’s essay and found I was not alone in my reaction. I thought the matter settled for the rest of the class, but a funny thing happened as we neared its end. As the final act of the seminar, Professor Kirchenbaum spread some arts and crafts items on the table around which we sat and showed us how to make a simple book. We created front and back covers to which we attached end sheets. We filled our books with a single signature of twenty blank pages and then sewed the pages in place using a long gold-colored needle and thick white waxed thread to make a pamphlet-stitch binding. We then used a bone folder to flatten the cover and page folds carefully. We were then asked to share our thoughts.

Holding the book I made in my hands, I remarked that it “felt complete” and “whole.” Though it was “empty,” it lacked nothing. Looking at the blank pages, I suddenly understood what Carrión had meant when he considered the empty book “perfect,” for I could fill my little book’s spaces with anything I wanted: poems, stories, images, neographies, etc. My book had endless potentiality, to borrow Aristotle’s term, and, so long as I did not mark it, it could become whatever kind of book I could imagine and create.

I am writing these words as I look at my little bookwork—Carrión’s term for objects in book form. I am dreaming of what it will become. Maybe I will fill it, and maybe I will leave it blank. Either way, it is a mysterious and wonderful object whose still-hidden secrets I look forward to uncovering.

For anyone interested in learning more about collation formulas, a five-part video series is available here.

My friend Jim Arieti, Ph.D., suggests that “collation is derived from conferre, an irregular verb in Latin, which means “to bring with” or ”bring together.”

Borsuk is the author of an excellent survey of the book’s physical and intellectual history, entitled, appropriately enough, The Book (2018, MIT Press).