A Poem of the Heavens

In the oldest surviving written work by a female Chinese poet, words become stars by which readers can, and must, chart their own journey.

Trust your heart if the seas catch fire, live by love though the stars walk backward.

—E.E. Cummings

Authors’s note: As of this post, there is no longer a paywall on Critic at Large, so all essays are available to the public, and a subscription is free. If you enjoy reading it, I hope you will spread the word about the newsletter. —CA

-

Earlier this week, a Critic at Large subscriber contacted me to let me know he had visited the MoMA on Monday. After reading my previous post about Refik Anadol’s “Unsupervised” data art installation, he explained that he had had the opposite reaction. He found the work visually exciting and intellectually stimulating and disagreed strongly with the conclusion I (and some critics) reached that it was a little more than an “extremely intelligent lava lamp.”

After my conversation with this reader, the idea of artworks containing many permutations and possibilities stayed with me. I remembered seeing an ancient work with similar characteristics while researching for my book, but I could not recall it. Yesterday, by coincidence, I pulled David Hinton’s excellent anthology of Classical Chinese poetry from my bookshelf and opened it to the first poet listed. That poet is Su Hui, who lived in the 4th Century C.E., and is remarkable not just for being the earliest poet in the anthology but also for being a woman. Although she is said to have written thousands of poems, only one survives: “Star Gauge,” a work that, since about the time of the Song dynasty (960 to 1279 C.E.), was known only in second-hand accounts and has only recently been reconstructed.

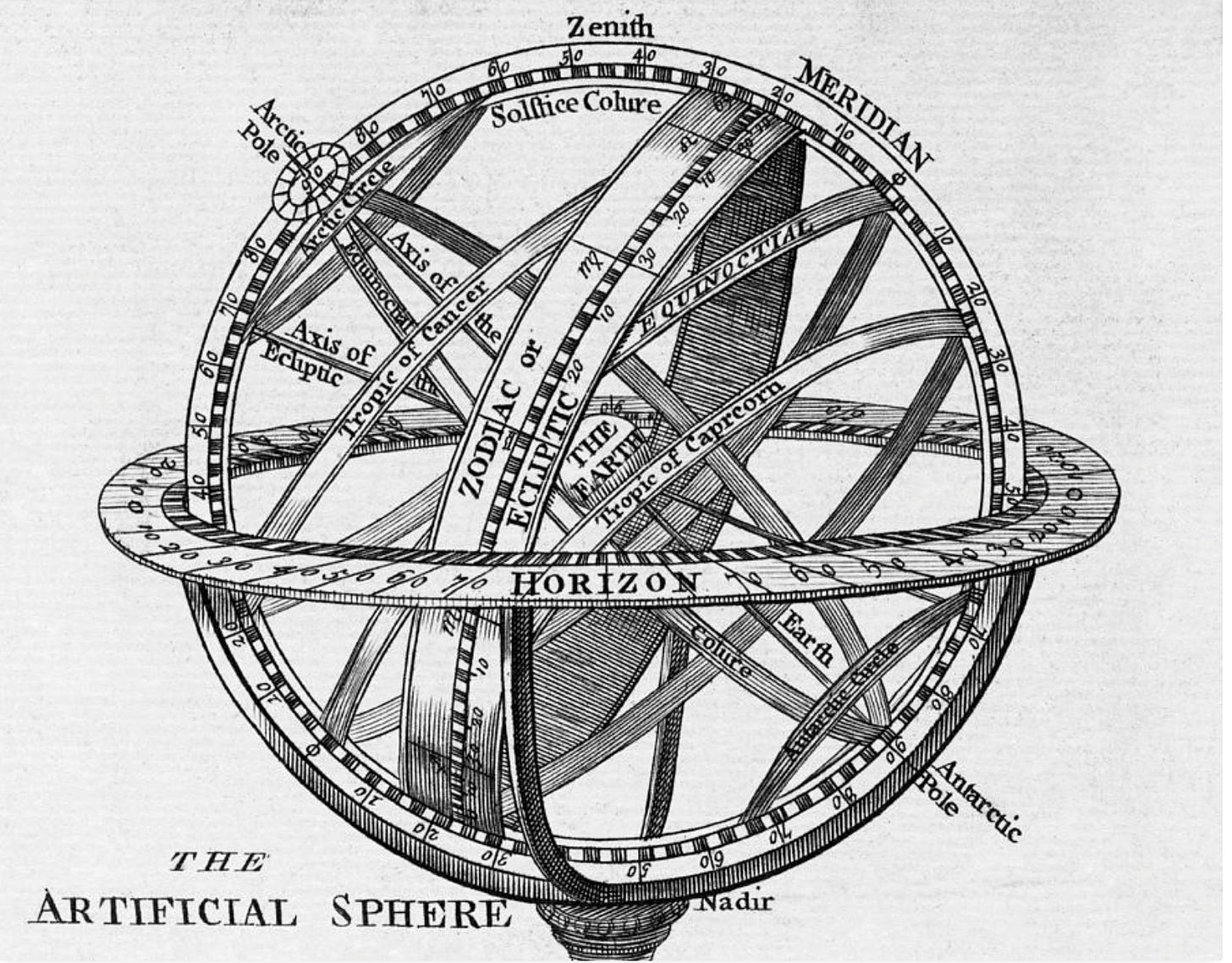

The origin story of “Star Gauge” is itself striking. It is said that one day Su’s husband, a government functionary of high status, informed her that he was taking a concubine and that he wished the three of them to relocate to a new city and live under the same roof. Su was furious at the proposal and refused, so her husband departed with his new infatuation, abandoning his wife to fend for herself. In anger and grief, she composed “Star Gauge,” whose title refers to what is known as an armillary sphere (or astrolabe), a mechanism that displays the movement of celestial objects around a body (typically the Earth or Sun), which had recently been invented in China (see image below).1

Image: Drawing Of An Armillary Sphere (Source: Middle Temple Library)

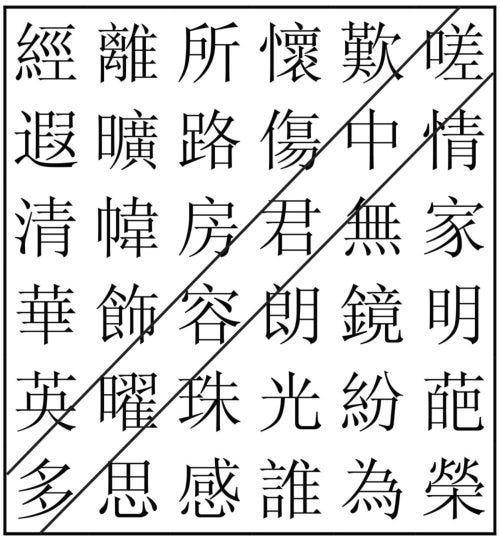

Su recreates the armillary sphere in “Star Gauge” by the physical layout of the words. She makes a quintuply palindromic grid of 29x29 character squares, made special by the fact that Chinese characters can be read in any direction (forward, backward, up, down, and diagonally). Su’s poem is in the tradition of what were known as “reversible poems,” which are enabled by this unique feature of the language, but her creation goes far beyond any other example of the genre. Hinton explains the poem thus:

Star Gauge was originally embroidered in five colors, thereby mapping out the poem’s complex structure. The colors divide the poem into a number of regions, each of which has a set of rules that tell us how to read the text in that region. Compounding this formal complexity is the fact that the text itself is often very ambiguous, making it difficult to decipher a particular meaning from a line.

As legend also has it, Su sent the poem to her husband, who was so moved by it that he abandoned his concubine and returned to his wife, and the pair lived together for the rest of their lives. While the poem’s goal may have been to win back her husband, even a cursory glance at Su’s creation reveals that it is not an ordinary love poem. As Hinton notes: “the poem is much more than a woman’s plea for her husband’s return.” It is a “complex philosophical statement, as well as an assertion of her own dignity and even superiority to the men who dominated her world.”

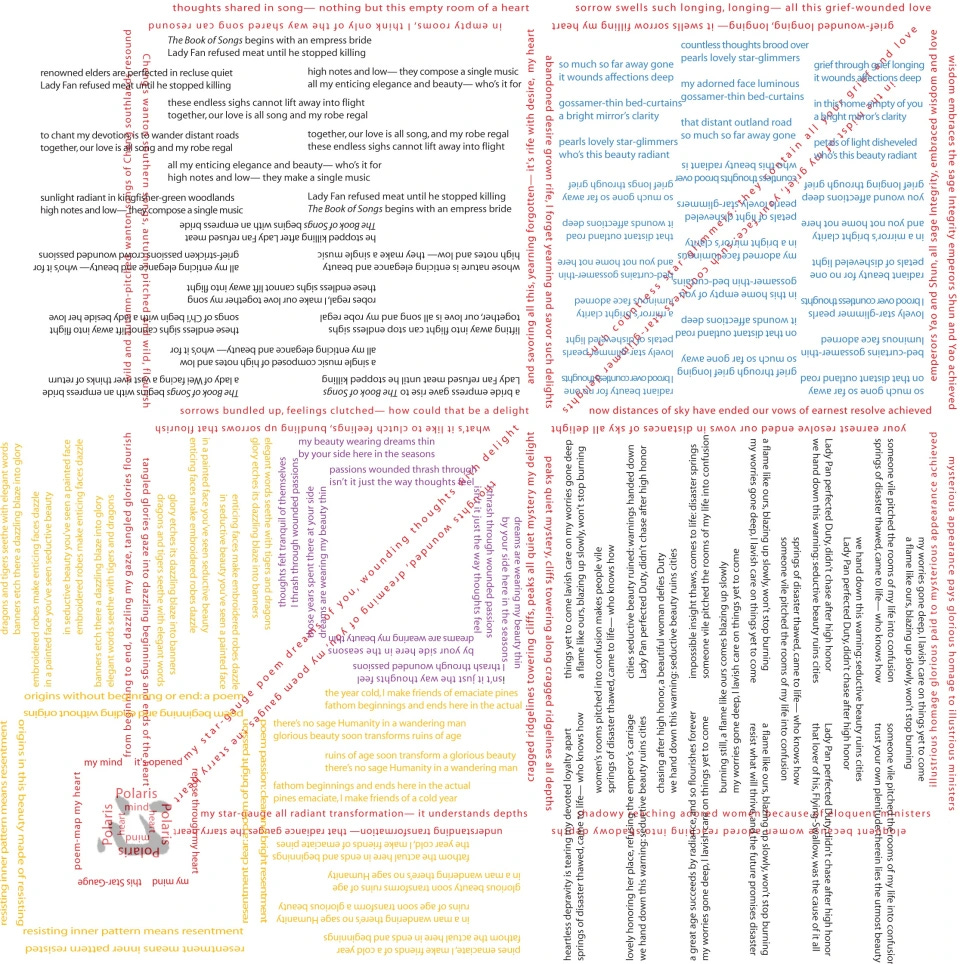

Seeing it today, I find the poem a fascinating literary creation as well as a work of visual art, a double achievement that can be found in ancient Greek poetry but was not seen regularly in the West until the rise of “concrete poetry” in the 20th century.2 Looking at Su’s work, one can imagine the intense emotion that she felt as she constructed her ever-changing poetry mechanism, a recreation of which is shown below:

Hinton further explains:

The meridians of the poem’s armature correspond to these rings of the armillary-sphere. The 7-character segments of the armature can be read in any order, so long as the reader follows the 7-character quatrain form. That is, at the end of each 7-character segment, which corresponds to a poetic line, you encounter a junction of meridians and can choose which direction to go. You can begin anywhere, and the poem ends after four lines have been chosen. This generates 2848 possible poems.

Take this section, for example:3

Read “forward” we discover these lines:

Alas! I sigh with languor Over the one who wandered from the way. Far-off the wilderness path Wounded my innermost feelings. The house no longer has a master Transparent curtains in the alcove. The face equally adorned In the bright mirror shines forth. Ornaments of the multiple reflections The pearls gleam, brilliant. So many thoughts assail me Who is seen honored there?

Read “backward,” we see something new:

To whom does the honor revert For prompting so many thoughts? Brilliant, the splendor of the pearls Reflections of multiple ornaments. Luminous the mirror shines Elegant finery of the face. Room with transparent curtains You no longer have a home. Feeling of a deep wound The path disappears into the wilderness. The way withdraws from here Me languishing, I sigh, alas!

What strikes me most about “Star Gauge” is that the reader constructs each poem by choosing where to start, in which direction to read, and where to turn. A reader can create a poem in one directional sequence and then “put it in reverse,” yielding an altogether different poem. Because each character has several meanings, one can create various versions not just of segments but the entire “sphere.” Below, for example, is one possible English translation (by Hinton) of the complete “Star Gauge” structure to give some idea of the work in full:

Sadly, for centuries in many cultures, East and West, the literary creations of women were considered inferior to those of men, and the subjects deemed fitting for women were often limited to domestic life and the tribulations of love and marriage. In China, women’s poetry was generally considered mere “folk art” and not worthy of being collected and preserved alongside the work of male masters. Su’s work is at once a part of that tradition but it is also more. It is a poetic creation with few parallels, but I write about it today because it reminds me of modern generative AI machines, which take the creations (words, images, music, etc.) of others and recreate them in endless iterations, each one slightly different. The reality seems to me to be that, to date, most of the output of these machines, despite their cost and complexity, is disposable and soon discarded. How wonderful, it seems to me, that almost two millennia ago a lone woman sat at home and created, with only brush and paper, a machine of infinitely more beauty and fascination. That realization brings me back to my conversation with the reader about “Unsupervised.” For him, Anadol’s installation is like Su’s grid: the source of constantly shifting messages, in which he sees meaning and beauty that I do not. Though the value of an artwork is not subjective, its effect on an audience can vary, and it is interesting to learn from others what I may fail to perceive.

While researching “Star Gauge” online, I found a website where anyone can interact with a digital version of Su’s creation. The original Chinese characters and several possible English translations are on each position in the grid. I started at the top left corner of the grid and read down four squares, which yielded this sequence: “The lute’s beauty and grace has withered.” I then read it backward as: “Fallen is the elegance of the wondrous instrument.”

Captivated by Su’s ancient creation, I spent about an hour moving up and down, across and around the “Star Gauge,” reading and composing, existing simultaneously as audience and artist. It is worth noting that this phenomenon is possible only with words, and that two thousand years after Su wrote, I can find in her/my poems her longing, creativity, intellect, and mischievous sense of humor. As I look around at the increasingly powerful algorithms that vie to replace writers and artists, I suggest to modern AI masters that they study Su’s creation and ask themselves whether their complex machines can reproduce the depth of human sensibility contained in one woman’s singular creation of love.4

The ancillary sphere was first invented in China. It was later, and independently, invented in Greece during the 3rd century BC. A sphere with the Earth in the middle is known as Ptolemaic. One with the Sun as its center is known as Copernican.

The modern use is believed to have begun with Guillaume Apollinaire’s Calligrammes: Poems of Peace and War 1913-1916.

Translation: www.veryprivateart.com