A Winter’s Tangerine

A short-lived publication, created by an African teenager, left behind a portal to the words and images of a remarkable group of young artists.

Differences simply act as a yarn of curiosity unraveling until we get to the other side.

— Ciore D. Taylor, The Conversation Starts Here: A Perspective of Self, Culture, and the American Society

I mentioned in a previous post a seminar on the “history and futures of the book” in which I am currently enrolled. One of my other classes is on the rhetoric of Black feminism, which Dr. Cecilia Shelton teaches. In each seminar, we explore language and how different groups create and use rhetorical devices and formulations. Reflecting on the cultural references of my much younger classmates and my ignorance of many of their artistic references, I went online to find work by emerging writers and poets (especially women of color), where I soon came across a project by Yasmin Belkhyr, an African poet born in Morocco who now lives in Queens.

While still in high school, Belkhyr founded a magazine called Winter Tangerine. In a 2016 interview, Belkhyr notes the impetus for her creation:

I started Winter Tangerine when I was 16. I had been writing and submitting for a few years and realized that the journals at the helm of the literary world weren’t publishing perspectives that I related to. I didn’t see youth poets or poets of color or women poets celebrated. I made a post on Tumblr with a call for staff and within a week, I had received over a hundred applications from such a wildly diverse group of people. After another week, we were a fledgling magazine with a full staff and a fundraiser and an open call for submissions. It was a really incredible time in my life, and a very sudden and monumental change.

The main goal of Winter Tangerine, noted Belkhyr, was “to amplify the voices of the unheard.” The magazine published only four issues and went on an “extended hiatus” in 2019; however, the four issues, along with the other works published on the site — which include short stories, poetry, and visual art — are fascinating and often excellent.

A standout example for me is Oluwabambi Ige’s 2017 award-winning short story, you do not take what does not belong to you. It is the tale of a girl named Laide who begins to steal at a young age and the outcome her actions bring her. It is an economical story, only a few paragraphs long, but its language draws power from its compactness and specificity, as in this passage:

Laide starts to steal when she is eleven, with easy and undistinguishable items; hair bands and lip-gloss and pens. When she is thirteen, her mother empties her room, removing items she does not know or did not buy. The memory of her mother hurricaning in her room is forever. Her mother flings things from the wardrobe, flips the bed over and harvests things she does not recognize. Her mother throws Laide into the nearest wall, watches her slide onto the floor, raises her and holds her neck between wrists and elbow, says “This is what will kill you.”

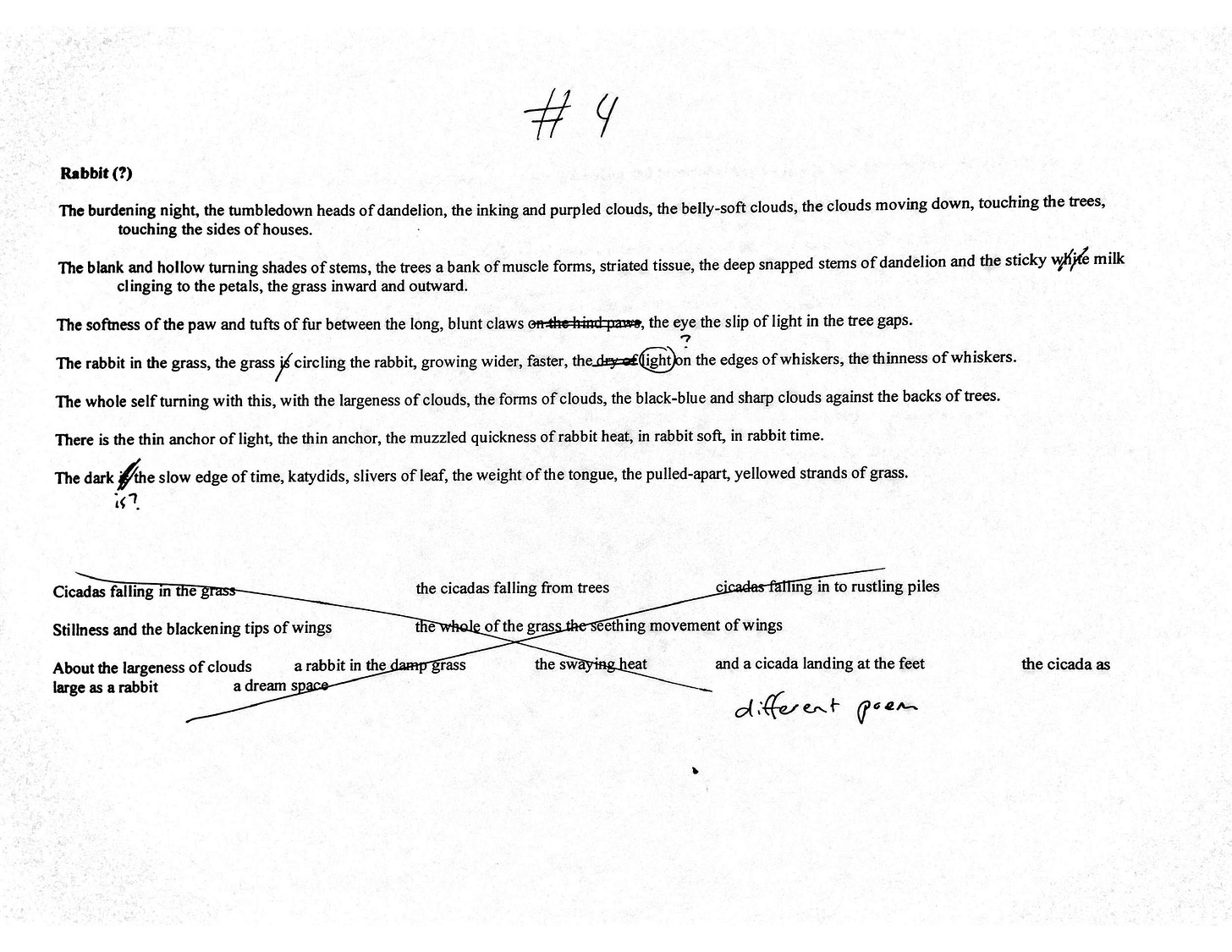

One of my favorite parts of Winter Tangerine is a section called “Shedding Skins,” in which poets present the evolution of a poem from first draft to final form. One of the more interesting “skin sheddings” is from Margaret Reges. It is about her poem rabbit, and we start with the first draft below:

Three drafts later, we can see the final form emerge:

By the final version, the language and imagery have grown denser, and the creature has been diffused into its surroundings:

The burdening night, the tumbledown heads of dandelion, the inking and purpled clouds, the belly-soft clouds, the clouds moving down, touching the trees,

touching the sides of houses.

The blank and hollow turning shades of stems, the trees a bank of muscle forms, striated tissue, the deep snapped stems of dandelion and milk

clinging to the petals, the grass inward and outward.

The softness of the paw and tufts of fur between the claws, the eye the slip of light in the tree gaps.

There is the thin anchor of light, the body in the grass, the grass circling the body, growing wider, faster, the light at the edges of whiskers, the thinness of whiskers.

The whole self turning with this, with the largeness of clouds, the forms of clouds, the black-blue and sharp clouds against the backs of trees.

Bracing out, discing, the fuzzed whorl at the end of the field, the field moving out from under itself, the graze of light on the ear, hollowed out into the eye,

the dark and the slow edge of time, katydids, slivers of leaf, the weight of the tongue and the yellowed strands of grass.Below the various versions, Reges reacts to the evolution:

Now, looking at the whole progression of drafts, I've come to realize that the first draft has an energy and openness that the final draft doesn't. (The importance of keeping early drafts!) It might be that I'll just scrap all the later drafts and work with the original in order to create something more closely in line with (what appears to be) the original impulse. Or maybe I'll just stop kicking a dead rabbit, as it were, and let it be what it is: a flawed attempt to contain/evoke a psychological state.

Poetry exists in two dimensions: the subjective one left to a reader to experience and the objective in which a critic must judge. Reading the poems in Winter Tangerine from both perspectives, I find much of it worthy of reading and even studying — a testament to the editorial talent and effort evident in each issue. Take, for example, “Lineage,” by Paige Quiñones:

One of my fathers played stickball in Harlem. This one never got a street-kid nickname. Another scared well-dressed ladies into crossing the street before he crossed their paths. I’m told it was his boots or his brown skin. A different father found friends stair-slackened: addicts a boy couldn’t turn his gaze from. One found god and never loved anyone. Another played a dented sax, its keys rusted pearly green underneath the pads. #6 had his name called to enlist— he didn’t like that one bit. Another kept a baby boy in tow. My favorite stood before the wild and never came back.

Perhaps the most striking element of Winter Tangerine upon first encounter is the artwork that each issue contains and accompanies the other works on the site. With almost every click, we find exceptional visual art in various forms. One of my favorites is this watercolor by Ali Cavanaugh:

Cavanaugh paints what she calls “modern frescoes” using a technique she developed while living in New Mexico. Working with clay native to the area, she developed a technique that gives her work a kind of striking luminosity, even in digitized form. On her home page, Cavanaugh explains how she came to be an artist:

My dependence on the visual world began when I lost much of my hearing through spinal meningitis at 2 years of age. This loss was a blessing in disguise as I learned to depend on body language and reading lips to communicate. So, from my youngest days, I became sensitive to the people around me and the unspoken language revealed through compositions of the human body.

The photography of the Iranian artist Shadi Gadhirian also struck me. Issue three features images from her series, Qajar, which took its inspiration from the past:

In 1995, I took a job in the photo museum of Tehran; there I learned a lot about the rich history of photography in Iran and how it was introduced during Naseredin Shah’s reign only 15 years after its invention. The shah was so taken in by this tool that he purchased a camera and brought it to Iran to personally photograph his 400 something ladies at his Harem. That’s how I came to pick Qajar style of photography in order to show the existing contrasts and contradictions for the young generation of Iranian women.

Another photographer who caught my eye is the African American artist Brandon Manciell. His photographs accompany a collection of writing called “Love Letters to Spooks,” published in memory of the Black queer artist Pepper LaBeija.

The poet Xandria Forest Phillips, who produced the collection, explains its goal:

The aim of Love Letters to Spooks was not for non-Black people to gain proximity to Black experiences, but for Black folks to have access to themselves free of non-Black projections. Not all deaths that Black people endure are physical. Pain exists that can only be detected and interrogated by Black consciousness’s. Not all grief is grace.

Taylor Johnson’s “this is how you enter the room” is a standout piece from this set. An excerpt is below:

If you think this poem isn’t for you, it is. The dead man could be your cousin, and not kin. So what does the poem do now? You want the poem to unrun the blood from his body, unkill the man whose name the poem won’t say. But this is just a poem. You are listening to Sam Cooke and he’s pleading, nearer to thee and it won’t be very long and you remember the ten guns that wanted you dead not too far from now, how you were almost a body in someone’s poem.

Across the journal's pages, one finds words and images that take the reader into the world Belkhyr wanted to bring to life. Reflecting on both the merit of the magazine’s existence and the sadness of its demise, I can’t help but wonder about all those other “unheard voices” and the stories and images they are creating in their own worlds. In an age when it seems we are saturated by attempts at art that are banal and forgettable, a creation such as Winter Tangerine is a rare find. It takes us into the minds of young artists, most of whom come from communities whose creations have been unread and unseen for far too long. It is an invitation to listen to them use language in imaginative ways that sometimes fail but often succeed.

I have returned to Belkhyr’s collection at least once daily since I found it. Staring at the landing page is like standing before the door that Dr. Shelton’s class opens a little wider each week. I encourage you to open it as well.

Striking post. So evocative of subtle emotions .

Thanks for sharing