Nox

In her elegy for a lost brother, Canadian poet Anne Carson creates a tomb from paper and ink.

The night keeps secrets.

―Maggie Stiefvater, Lament: The Faerie Queen's Deception

In 2000, the Canadian classicist and poet Anne Carson’s older brother Michael died suddenly in Copenhagen.1 Since he abandoned his family eight years earlier, Carson spoke to him only a few times. She described her relationship with him thus in a 2012 interview:

I didn’t know very much. We both went to university—different ones—more or less at the same time. I was immersed in my Greek and Latin, a world he had no interest in or patience with. And he diverged from me in taste and moral standards and everything else that makes you a person, so I didn’t really know him anymore.

In response to her brother’s death, Carson created a private scrapbook into which she placed sections of photos, papers, letters, stamps, and ephemera from her past with Michael. From the start, Carson deliberately “aged” the artifacts in her book through various techniques. When asked why she did this, she replied:

It was a fancy of mine to make the left-hand pages, the Catullus pages, look like an old dictionary because when I was learning these languages, I always had very old, faded dictionaries with yellowed pages. The experience of reading Latin, to me, is an old dusty page you could hardly make out.

For many years, Carson showed her scrapbook only to friends one by one. She did not think of it as a public work, just her own memorial. One day, she met a German publisher who told her he could reproduce it. The man took her scrapbook to Germany and then disappeared for three years. Carson thought the book was lost forever, but one day it arrived out of the blue at her house via FedEx. In that moment, she decided to find a new publisher to reproduce it.

My brother once showed me a piece of quartz that contained, he said, some trapped water older than all the seas in our world. He held it up to my ear. “Listen,” he said, “life and no escape.”― Anne Carson

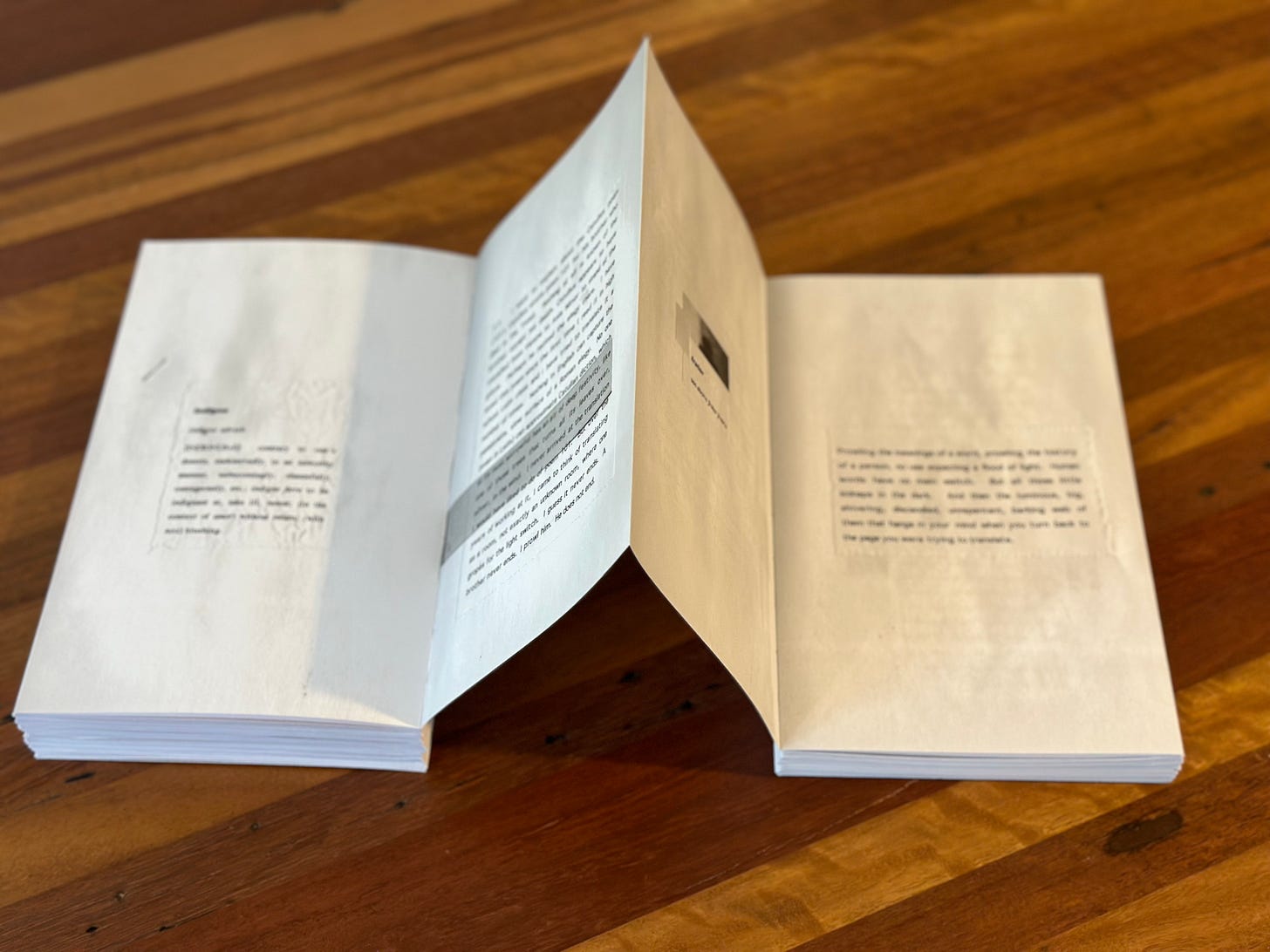

Created by New York-based New Directions in 2010, the book is presented in a hard, rectangular, grey cardboard case 9.25 inches high, 6 inches wide, and 2.5 inches thick. Its spine is printed to look like cream-colored cloth, and on it is printed the book’s author, publisher, and title—Nox—all in an upper-case sans serif font. On the cover is a strip cut from a larger photograph showing her brother as a child. The box and book are heavy and, in form and color, remind one of a gravestone or, when open to its almost empty white insides, a crypt.

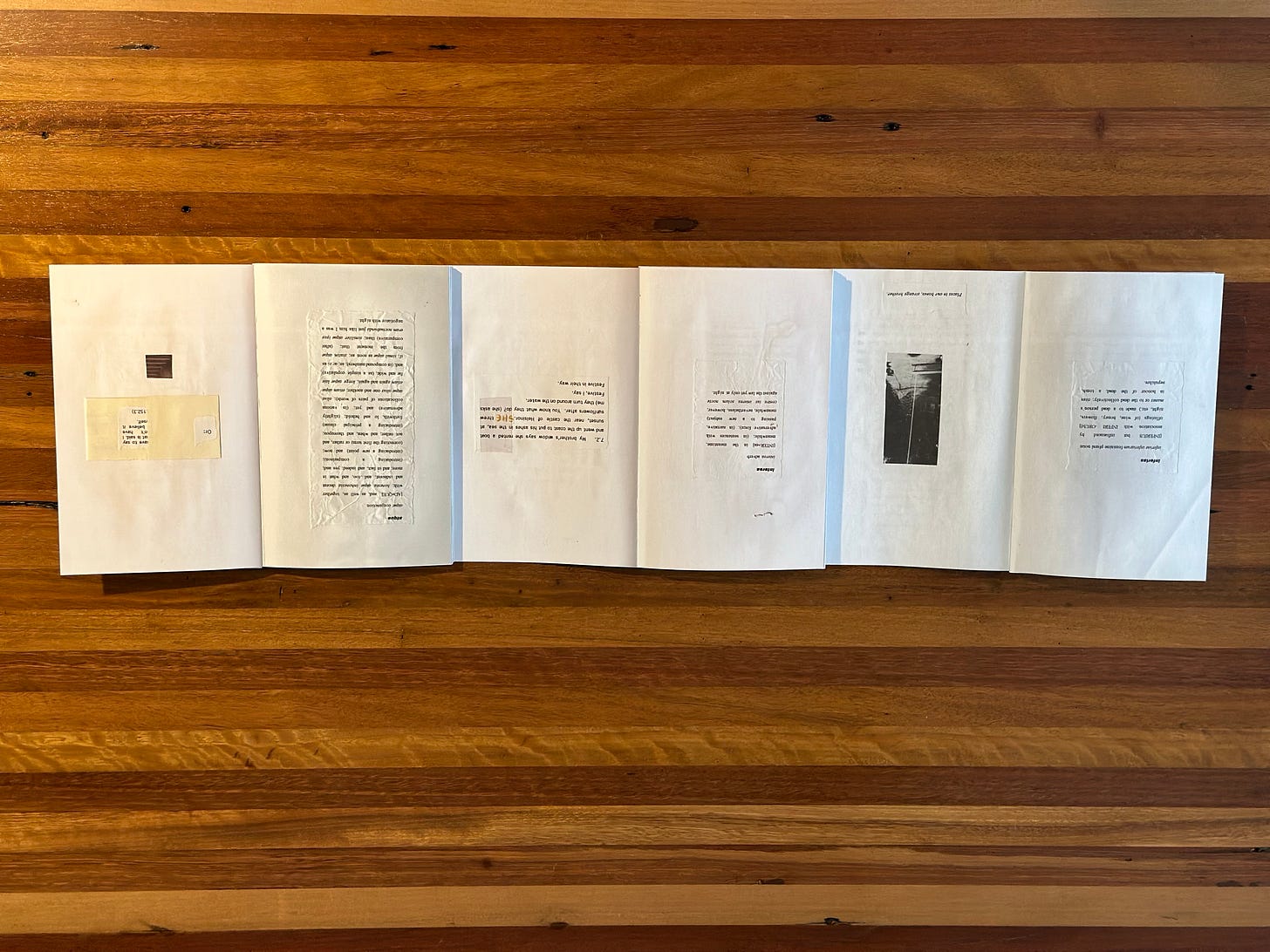

The first thing one notices upon removing the printed book from the box is that it is not formed from bound pages; rather, it is one long piece of printed matter, folded accordion-style upon itself. Holding the book for the first time, its physical format intrigued me: why make a single long work when the pages could have been bound as in the original? On the first page, I found the answer: a “pasted” paper that contains a slightly smudged print of the Roman poet Catullus’ Poem 101 in Latin. In antiquity, most texts were written on scrolls, which are long continuous structures. It makes sense that an elegy by a classicist should recall that ancient form, and so the printed Nox is presented to us in a kind of liminal state somewhere between book and scroll.

Catullus’ poem is an elegy to his brother, who died at a place called Troad, near Troy. The poet traveled there to deliver his elegy in person over his brother’s grave. The poem plays an important part in the layout of the book, for on most left (“verso”) pages, we find what looks like an entry cut out from an old lexicon of Latin. On most right (“recto”) pages, we find something that lies in contrast to the linguistic information on the left. When asked about this arrangement, Carson noted that as a classicist, she is accustomed to reading parallel versions of text printed across from each other. Being translations, the texts are at once similar and different, and this relationship persists throughout Carson’s book. This arrangement varies from time to time, with some pages left blank and some folds presenting images on both sides.

The quality and realism of the printing are remarkable: one has the sensation of seeing the actual items from her original scrapbook. This is true of all the items presented: stamps look like they have been mailed, photos appear to be real, and letters written in ink appear to be sitting on top of the page. Little strips of text look as though they were pasted and not printed. There is very little bright color, but what color there is, primarily red, seems three-dimensional. On page after page, the reproduction is so visually accurate that it becomes disconcerting. In other words, it is easy to become frustrated that one cannot touch something that seems so real.2

One clever feature of the book’s physical form is that a reader can expand a fold by twos and simultaneously see four, six, eight (and so on) pages. Moreover, one can fold later sections on top of earlier sections.

This feature, impossible in a conventional book, allows for the construction of hand-built “passages” from Nox, which is facilitated visually by the fact that the pages are without numbers, so the typical numerical page sequence is undisturbed by such arrangements. This aspect of the accordion form, which would be clumsy if not impossible in a scroll, allows us to create many text and image sequences and thus discover relationships across the book’s pages. Moreover, one can unfold the entire work and move across it without touching a page, allowing a reader to observe the whole work in one sweep. Doing so reveals that some pages form little “tents” that rise from the planar surface, like momentary monuments.

Manipulating the pages in such ways takes concentration, and the reader cannot just “flip the pages” as in an ordinary book. Nox’s physical form, like a Greek or Latin text, demands care and thoughtfulness in order to interact with it. The more one handles it, the more one understands how to balance its weight, movements, shapes, and intricacies. You don’t hold Nox — you interact with it mentally and relate to it physically.

Carson has said that the creation of the original scrapbook did not have a specific process or method. She just added things to pages and waited to see what the whole would become. She called the collection an “epitaph,” a word derived from epitaphion—a funeral oration often read, as in the case of Catullus, over the dead. Reading Nox while holding it alongside its case, we hold in our hands Carson’s memories, words (ancient and modern), and images (in whole and in part), and by doing so, we can perform our own epitaphion for Michael Carson. The book’s physical form makes us mourners as well as readers, a sensation reinforced when, our experience complete, we place the carefully folded pages back into their tomb, perhaps never to be reopened.

In several ways, Nox reminds me of Yiota Demetriou’s remarkable art book, To You, (the comma is part of the title), which I experienced at the UMD Booklab on Tuesday. Demetriou’s book comes in a small brown cardboard box tied with twine. Inside the box is the book, bound, like Nox, in accordion form, along with a note about how to “care for the book.” Unfolding To You,, one sees only a long stream of pages coated with a smooth black substance. At first appearance, there is nothing to read. When I put my hand on the book, however, pressed down for a few moments, and then lifted it, I saw text emerge on what bookmakers call the substrate. This is because the book’s text is covered with thermochromic ink, which disappears in the presence of heat.

The text itself is a series of love letters that Demetriou wrote but kept to herself. She explained the idea behind To You, in a 2018 lecture:

The book is presented as an intimate reading experience hidden in the pages of an apparently unreadable book. The content draws parallels between the intense erotic delusions played out in the exchange of love letters, and the dynamics of human relationships. Imbued with warmth from a reader’s gentle touch, its black pages gradually become translucent. The writing becomes visible, and traces of fingerprints are left on its pages. Unlike many reading experiences, this book responds to body heat by inviting the reader to lovingly caress it.

She also noted that, like Carson, the project was a way of healing after loss:

Creating a book was not my intention. It became a book. The narrative was born out of something highly personal: love letters, as mentioned, that were never sent. A conversation with myself attempting to rationalise and put into perspective what had happened in a relationship. A mode of healing I suppose, by questioning the human condition, the different dynamics at play, and simultaneously negotiating vulnerability with oneself.

Interestingly, Demetriou has described the experience of creating her book as an apogymnomena, which is “a Greek word (my first language is Greek) that expresses what the book conveys, meaning “vulnerable emotions or experiences that are startling, raw, humiliating, naked, intimate, overtly exposed and almost unsettling in their own familiarity.” I shared a preview of this essay with Dr. Demetriou, and she kindly offered advice on how to read her book:

To You, needs effort and time, just like building strong relationships or healing from a wound. But here’s a way to make it a shared experience: read it with someone, each with a hand on the same page (one underneath the page and the other on top). Imagine the connection that forms as you turn the pages together, and reading is transformed into a journey of connection, not a solitary act.

Contemplating the shifting shades of grey and black in Nox and To You, side by side, I recalled that “Nox” was the Roman name for the Greek goddess Nyx (“Night”). Nyx was a primordial being, thought to exist from the beginning of time, from whom sprang many of the elemental forces that shaped the human condition, including Aether (“Light”), Hypnos (“Sleep”), and Thanatos (“Death”). Though young and beautiful in appearance, her visage was said to be somber, befitting the grave creatures whom she had brought into existence. Like many Greek deities, she brought good and evil to humans: restful sleep that replenished strength but also darkness and death. The name is fitting, for Nyx’s presence is felt throughout Carson’s and Demetriou’s creations. Their wide spaces allow the reader to rest and absorb each text fragment as an archaeologist would: deliberately and with care for each letter, line, image, and their surrounding spaces—all augmented by the desire (or need) to touch that the printer’s skill engenders. In Nox, moreover, the grey shades of the notebook’s paper and the sense of discoloration on all the artifacts give one the sense that a dark brooding cloud hovers overhead whenever the book is opened.

Some conversations are not about what they’re about.― Anne Carson

In the 2012 interview, Carson said that Greek and Latin texts do not speak to us. On the contrary: we speak to them, carrying the present with us like an offering and asking them to interpret it for us. Modern markers for the dead have a similar function: we go to a cemetery to share our present with those we have lost and ask their shadows to help us make sense of our existence. Likewise, Nox’s shape, form, and printing create both epitaph and tomb, filled with phrases in a dead language that come to life when we take the book from its case and question it about Michael, Anne, loss, or even death itself.

Her memorial is an oracle of life and death in book form that, like the oracles of old, speaks in riddles. Straight answers are denied, so words and phrases must be parsed for their meaning. This function is reaffirmed on the book’s final page, where Catullus’ elegy, which we see first in full but rough English about two-thirds through the book, is presented one final time. The surrounding paper is dark grey, almost black, as if night were falling and little light remained. Looking at the page, we see that the poem’s text is now deformed, discolored, and fading away. Like Michael, it has decayed and is too blurred to read, which means that it can only be remembered.

Multās per gentēs et multa per aequora vectus adveniō hās miserās, frāter, ad īnferiās, ut tē postrēmō dōnārem mūnere mortis et mūtam nēquīquam alloquerer cinerem. quandoquidem fortūna mihī tētē abstulit ipsum. heu miser indignē frāter adēmpte mihi, nunc tamen intereā haec, prīscō quae mōre parentum trādita sunt trīstī mūnere ad īnferiās, accipe frāternō multum mānantia flētū, atque in perpetuum, frāter, avē atque valē. - Traversed through many lands and many seas I reach these wretched fun’ral rites, my brother, So I may give one gift to you, at ease, And might converse in vain with silent cinder. Since fate, poor brother, stole your soul away From me, and long before the time was fair All this aside, accept these gifts today— To ancient mores, you are the latest heir This tribute drips with many tears I cry And always, brother, hello and goodbye. —Catullus, Poem 101, Trans. Sara Albert

Carson has said that Michael struggled with drug use and probably left to avoid criminal charges.

It’s almost the print version of the uncanny valley, the term coined by the Japanese philosopher Masahiro Mori to describe the unease generated in people by technology that seems too close to being human.