When Art Is Liberty

A remarkable Italian film uses Shakespeare's play to find humanity in lost souls.

How many ages hence

Shall this our lofty scene be acted over,

In states unborn and accents yet unknown!

―William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar

Anyone who has spent time in Italy knows it is a nation that marches to its own drummer. Art, in its many forms, has an especially significant role in the life of Italians, and their nation’s artistic traditions extend beyond famous monuments and museums to venues that would be unthinkable in most other nations. Perhaps no phenomenon better captures that characteristic than Italy’s collection of over one-hundred theater companies that flourish in the nation’s prisons, including the ones that house its most violent and hardened criminals.

In the dangerous structures that hold Mafia killers, Italy allows—encourages!— professional actors and directors to produce plays performed by inmates, and criminals have been cast even in feature films. Director Matteo Garrone, for example, used Neapolitan gangsters in his 2008 drama, “Gomorrah” and cast Aniello Arena, a convicted hit man serving a life sentence in a Tuscan prison, in his film “Reality.” By sheer numbers, prison plays are the plays most seen in Italy, and in recent years prominent architects such as Renzo Piano and Mario Cucinella have designed theatrical spaces within prisons for the most well-known companies. It would be as if Tom Hanks or Steven Spielberg directed prisoners at Leavenworth on a stage designed by Philip Johnson.

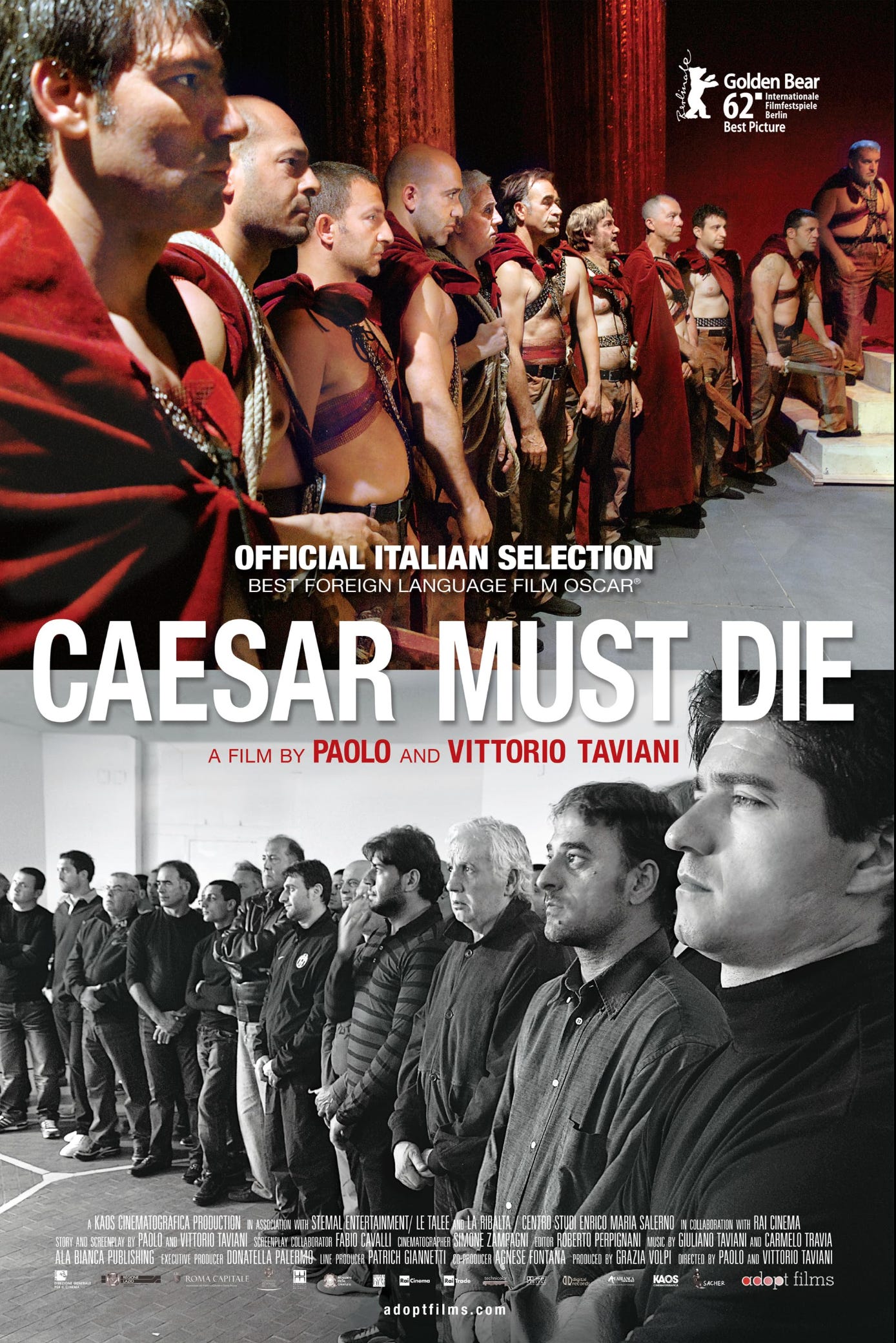

I came across the story of Italy’s prison theaters doing research for my novel, The Long Eclipse, but I had never seen an actual performance. That changed last week when I saw the 2012 film, Caesar Must Die, by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani. The brothers persuaded the authorities of Italy’s maximum-security Rebibbia Prison in Rome to let a company of inmates stage Shakespeare’s play for the prison’s annual dramatic production. They convinced the Genoese actor Fabio Cavalli to direct, and the Taviani brothers recorded the auditions, rehearsals, and performance for their film. All the actors are prisoners serving time for the worst of crimes, and many of them are serving what the Italians call “Life meaning life,” which signifies they will never see another day of freedom while they breathe.

The brothers explained their inspiration for the film as follows:

A dear friend recounted to us a theatre experience she had had a few nights earlier. She cried, she said, and this had not happened in years. We went to that theatre inside Rome’s Rebibbia prison, the high security section. After passing a number of gates and blockades, we reached a stage where twenty or so inmates, some of them serving life sentences, were reciting Dante’s “Divine Comedy”. They had chosen a few cantos of Hell and were now reliving the pain and torments of Paolo and Francesca, of Count Ugolino, of Ulysses—all in the hell of their own prison. They each spoke in their own dialect, occasionally addressing parallels between the poetic story evoked by the cantos and their own lives. We remembered the words and tears of our friend. We felt the need to discover through a film how the beauty of their performances was born from those prison cells, from those outcasts that live so far from culture.

The Taviani shot their film in high-definition black and white, giving it a stark and barren look that complements the sparse spaces in which the actors meet and prepare for their performances. From the film’s earliest moments, it is clear that the prisoners take on their roles with a seriousness that speaks volumes about the opportunity they have been given to be artists in their otherwise isolated existences—if only for one day. As the critic Philip French noted in his review of the film:

In one arresting moment a Camorra strong-arm man says “Naples” instead of “Rome” and explains: “It seems as if this Shakespeare was walking the streets of my own city.” In another, the imposing Caesar, who looks like (and probably is) a mafia capo, turns on Decius, the conspirator dispatched to bring him to the Senate, as if he were a genuine traitor luring him to his death.

In short, we experience more than acting—we behold memory and recollection—and in the prisoners’ voices and faces we hear and see the anguish and fear they have shared with the historic characters depicted in the play. As another critic noted, the film is not a traditional documentary that tries to capture the story of the production; rather, it aims for something more basic, even unsettling:

…there’s little in the way of a one-to-one correspondence between Julius Caesar and the everyday reality of a maximum-security prison. The effect is more suggestive. You’re inside the play and then outside, in and out, until where you literally are doesn’t matter anymore. You’re in a heightened, concentrated space in which every action ripples outward.

Any drama in which the story is known ahead of time is enhanced by what the retelling illuminates or reminds us about the human condition. What Caesar Must Die reminded me of most was not the play itself, which isn’t really the subject of the film, but rather the humanizing power that art can have on even the most desperate of souls. This realization is captured in the movie’s final scene. The prisoner who has played the part of Cassius is returned to his desolate cell. Standing there—his past and future home—he stares at the camera and says, “Since I have discovered art, this cell has turned into a prison.” It is a devastating moment, and the words are genuine and heart-breaking, even knowing the nature of the man who utters them.

As I listened to the metallic doors enclose the inmate in his confinement, I recognized a man who had touched something immortal in Shakespeare’s words and had been freed from his captivity for one glorious moment. As I learned from the reading I engaged in while writing the essays about the loss of my son, art has the power to lift us from the deepest despair. Caesar Must Die captures that power in the most unlikely of settings and is a testament to the shared humanity that the coldest prison cell can never erase.