Still-Life (Talking)

A 17th century Dutch masterpiece makes a subtle case against the vanities and perils of wealth.

When it is said that the artist imitates the poet, or the poet the artist, a double meaning may be conveyed.

—Gotthold Lessing, Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry

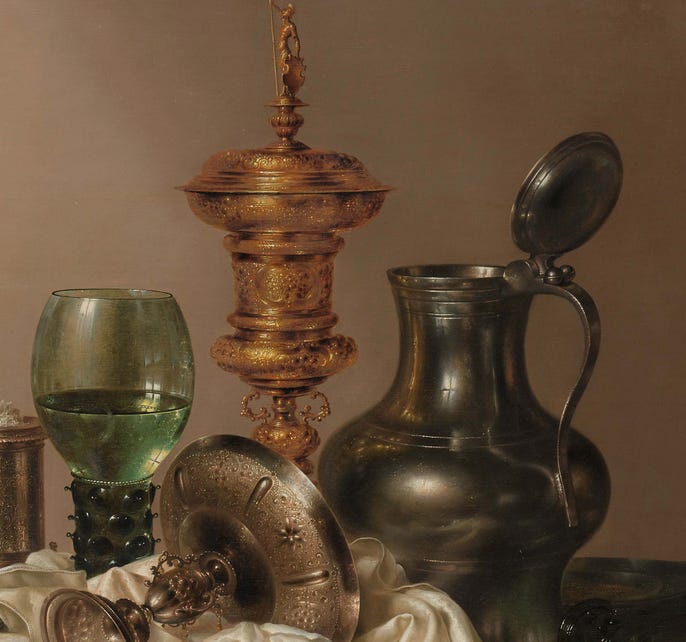

I have a special interest in looking at persuasion in the arts, and in this post we’ll examine a remarkable painting made by the Dutch master Willem Claesz Heda in 1635. “Still Life With a Gilt Cup,” as the work is now known, came to mind this week because of a well-done commentary on the piece by Jason Farago in the New York Times. Farago looks at the painting from the perspective of the mercantile culture that dominated Holland at the time of the work’s creation. Farago, however, does not consider any philosophical arguments the painting presents, so let us look at it closely and try to decode its less obvious moral message.

We can start by noting several details, the first of which is the plate of oysters in the center-left of the work.

Unlike today, back then oysters were usually served at breakfast, so we know this works talks to us about the start of the day. As in our own time, however, oysters were considered an extravagance, which suggests the table belongs to a wealthy individual — since this is a service for one person only — and probably a man. Even more so than today, oysters had a clear sexual symbolism, often representing both virginity (when closed) and fertility (when open and eaten). Below the half-eaten oysters, we see a plate with peppercorns rolled into a page torn from an almanac. As Farago notes, pepper was also a luxury at the time, and “the Dutch today still express sticker shock with the word peperduur — as expensive as pepper.” That the torn page comes from an almanac may also suggest a few ideas, such as the passage of time and the fact that the day this page represents is gone forever.

Behind the oysters, we see a glass oil flask (likely from Venice, given its decoration) next to a fancy silver salt cruet. Both items allude not just to wealth but to the global span of the Dutch trading empire at the time.

The luxury of the home is also highlighted in the decorated tableware that fills the table, especially in the gilt cup that lays on its side carelessly.

Farago’s favorite detail is the half-peeled lemon, which he considers a bit of showing off by the artist.

“By letting the peel dangle,” Farago notes, “the art historian Svetlana Alpers once observed, he turned the lemon into something both solid and open — just like the glasses and tankards.” Lemons were imported into Holland and thus expensive. While they too denote luxury, they also served as a symbol of the bitterness of life.

The last detail worth noting, for now, is how the two bottom plates (and the expensive black knife at their right) lie not on the table but half-hovering, as if suspended in air and about to fall down.

Taken as a whole, we see then the morning table of a wealthy Dutchman covered in the splendors that Holland’s global commercial empire brought back to its people in Amsterdam. The man is rich enough both to acquire these items and to abandon — perhaps even “waste” them — carelessly as he starts his day.

To glean the possible message of the painting, we must recall that at the time of the work, Holland was ostensibly a nation of Calvinists, a Protestant branch that censured needless wealth, money-lending, and financial speculation. In its most extreme form, Dutch Calvinism forbade owning anything more than the minimum needed to live a good Christian life. Material goods gained by a man beyond the bare necessities were to be given to the poor. Indeed, one of the great debates of Dutch history is whether its great 17th-Century trading empire arose because of, or despite, Calvinism, since the religion seemed categorically opposed to the foundations of capitalism and its emphasis on accumulating wealth for its own sake.

The philosophical battle between wealth and minimalism is the key to the painting’s message, for we can read in the work a warning from the painter to the wealthy customer who first purchased it. Material goods, the work seems to say, are seductive and may give pleasure, but one will soon tire of them and may even come to abandon the objects once longed for. Fate, moreover, must run its own course, and the plans one makes — to have a slow, luxurious breakfast, for example — can easily be disrupted. Indeed, the haphazard arrangement of the table, half-eaten dishes, and the somber, almost monochromatic, color palette may just be showing us the final moment of a merchant who passed away in the middle of his meal.

One more item is worth noting. If you look closely at the goblet, you can see the reflection of a window.

This detail is not just a technical marvel, it is also suggestive of the light from the outside world. Light has long been a symbol of the divine in the Christian tradition, and perhaps here the light represents God’s eternal eye watching over the life of the absent man. Alive or dead, the artist may be suggesting, persons — and the objects and desires that define their existence — are always seen by the higher power that will judge their lives on earth when the Day of Judgment comes. The painting, taken as a whole, seems to me a subtle Calvinist-inspired warning to its viewers: be careful as you grow rich, and do not allow the world’s luxuries to consume you, because only God knows when and how each day — and your entire life — will end.

In 1634, at the moment Heda was painting Still Life With a Gilt Cup, the great Tulip Bubble gripped Holland. Speculators lost fortunes betting on the rising values of imported tulips, and the unfortunate outcome of that financial calamity was on the mind of other Dutch painters such as Hendrick Gerritsz Pot, whose 1640 painting, “Flora’s Wagon of Fools,” shows weavers dropping their looms to join the flower goddess Flora in a doomed search for riches.

Pieter Roelofs, a curator at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (where Heda’s painting is now on display), has noted that many paintings at that time “were a warning — a moral reminder — to watch what you are doing: since there will be the inevitable moment of death.”

Still-life paintings such as Heda’s were for a long time considered a lower form of art, inferior to paintings of Biblical and mythical scenes, portraits, and landscapes. Ironically, given the realist techniques that define classical still-life works, the impressionist and post-impressionist painters revived the form, which led to a re-appraisal of painters such as Heda and his now more famous Dutch peers. In doing so, the latter painters perhaps realized that what may seem like a static image can be a deeper statement about the world or, as in the case of Heda, a warning about the illusions of wealth and the transitory nature of human life. Indeed, Heda’s attempt to persuade us about the dangers of greed seems a fitting one for us to consider in a week when, like the Dutch of the 1600s, speculators in our own time just lost over $1 trillion in wealth betting on the rise of cryptocurrencies. Perhaps a little less might have been lost with a deeper contemplation of the message contained in a half-finished meal.